Group therapy helps scientists cope with challenging ‘climate emotions’

As climate records tumble and wildfires rage, people all over the planet are feeling the toll.

Negative emotional responses such as anger, fear, sadness and despair recorded in children and young people are also felt by climate scientists. But positive emotions such as hope are also part of the picture.

Anxiety is a natural response to these conflicting emotions. The consequences range from trouble sleeping, to difficulty working and socialising. Climate anxiety can also exacerbate or trigger other mental health problems.

In our new research, we explored using group therapy to create a safe space for scientists to share their feelings. Such safe spaces are vital for people to understand and process their emotions and ultimately find the strength and resilience to continue their important work.

Anxiety can trigger action

Climate anxiety has not been classified as a mental health disorder. Some researchers warn against calling it a disease, because this implies it’s caused by some type of dysfunction within the individual, requiring therapeutic intervention, perhaps even medication.

Rather, they argue climate anxiety can be a catalyst for action. It is also a reasonable response to what is a significant existential risk.

We know collective and individual climate action can alleviate negative climate emotions.

We also know negative emotions such as guilt are less motivating than positive emotions. The limitations of fear as a motivator are well documented.

A fly on the wall

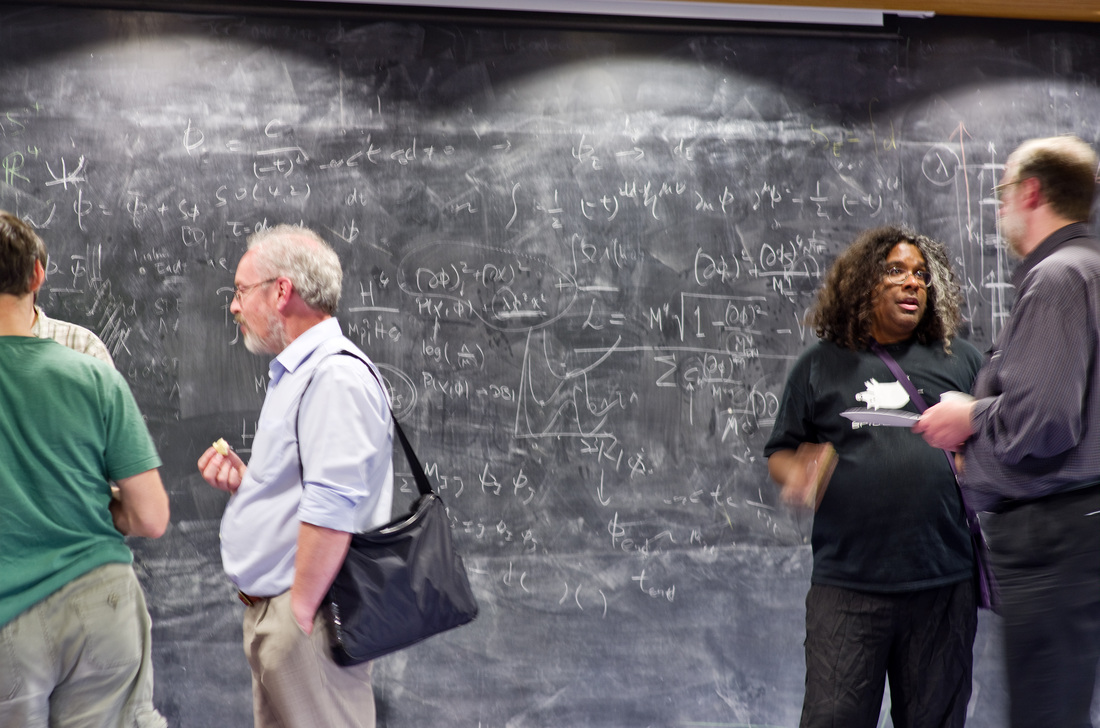

Over two days, seven environmental scientists participated in intensive group therapy facilitated by a qualified psychologist. They shared their feelings about climate change, discussed academic pressures, and how their individual identities intersected with their professional roles and research.

We analysed transcripts from these sessions and found:

- 1. Deep awareness of the climate crisis puts scientists at greater risk of mental health problems. As one participant said,

It’s very easy to fall into this vortex, right? Of thinking about climate change as a problem and not just climate change, but […] global environmental change, ecological loss.

- 2. The nature of academia means climate emotions overlap with “intersectionality” (the interconnected nature of race, class, gender and so on) to worsen their experience. According to one scientist,

I always tell students you have to do experiments in pairs, documented, because as a person of colour, I would be doubted, you know, if we made that great discovery.

- 3. Scientists do not talk about the emotional toll of their working knowledge. As one said:

How do you talk to your colleagues [about climate change] We don’t talk about it. We don’t talk about how [climate change] is making us feel. And I didn’t know if that was just me, but I was also like, why don’t we talk about it?

- 4. Safe spaces such as group therapy can have an immediate valuable cathartic effect. One participant observed:

I’m privileged to be sitting here with an amazing group of people. I think what came out of this conversation, [from] the way things have been framed and reframed and picked apart and put back together again, is incredibly useful.

More work to be done

Our findings support the value of group therapy as a cathartic outlet for climate emotions among environmental scientists. But further research is needed before this intervention is offered routinely within research institutions, among existing colleagues and peers.

In this case the scientists were strangers from across the United States, brought together by a Swedish documentary film crew. That may have made them more inclined to open up and share their emotions.

We also need to know how long this cathartic effect lasts, and what long-term support might be necessary to foster lasting benefits.

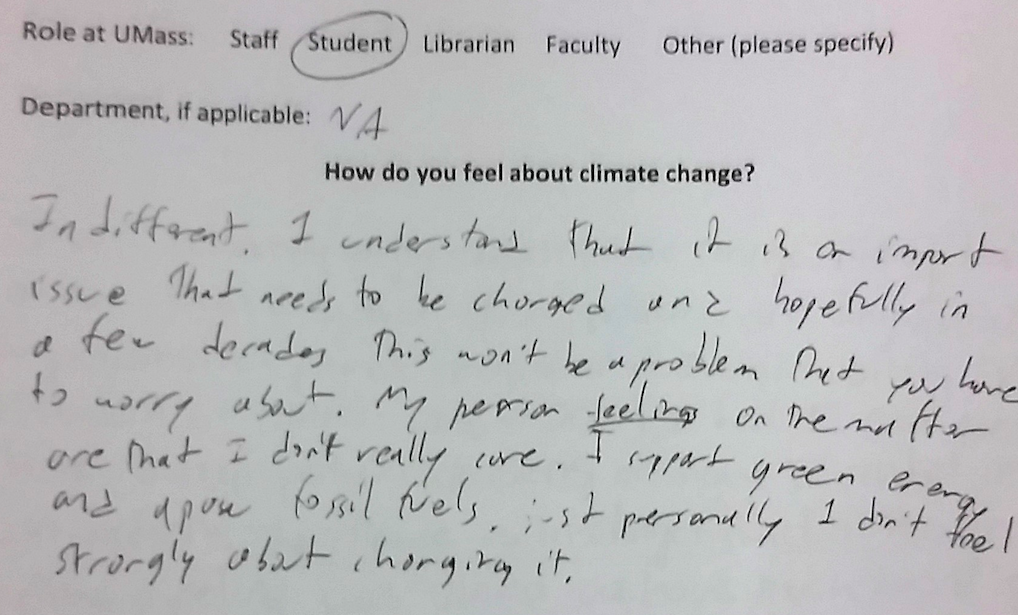

Different generations and groups experience a wide range of different climate emotions. Equally, a wide range of solutions must be made available to help people, particularly environmental scientists, deal with the negative emotions affecting their daily lives.

Group therapy is not a silver bullet, but it does show promise. The tool allows people to share their emotions, realise they are not alone, and gain a sense of community and catharsis from spending dedicated time with others who find themselves in similar situations.

As the climate crisis continues to worsen, more people will be exposed to harm. Even more will be exposed to reports and news coverage discussing our increasingly uncertain future. As a result, climate anxiety is likely to become more prolific, perhaps most so in climate scientists. This presents a real and urgent need to explore how we manage and process climate anxiety.

While collective and individual action offer ways to reduce climate anxiety indirectly, we also need more platforms for knowledge sharing, more safe spaces and more research into managing the mental health impacts that we are all clearly already feeling.![]()

Joe Duggan, PhD Candidate, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Australian National University and Neal Robert Haddaway, Senior Research Fellow, Africa Centre for Evidence and Stockholm Environment Institute, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed