The Scientists

Climate change is a complex and intimidating threat. You can't see it when you look out your bedroom window. Its impacts are often not immediately noticeable, nor are the benefits of acting against it.

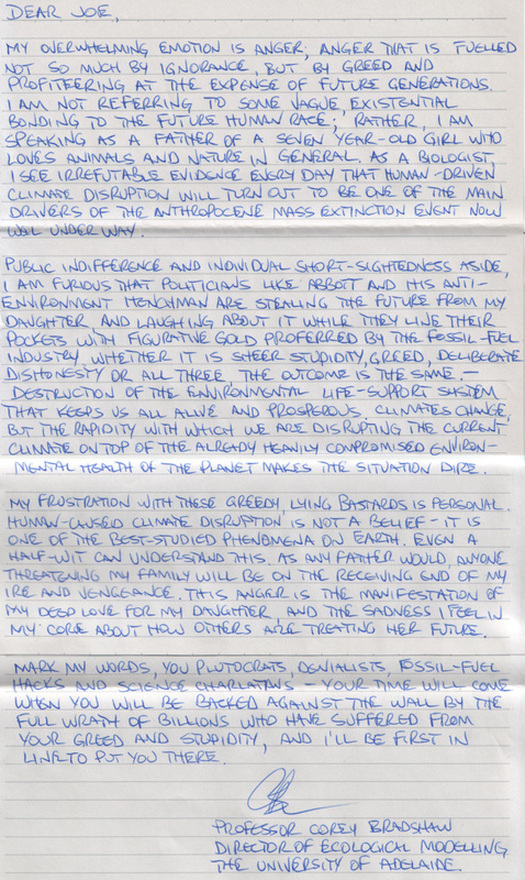

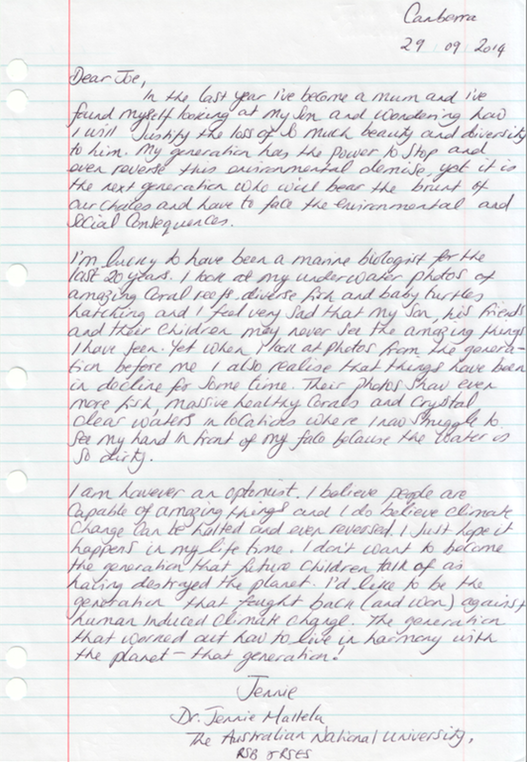

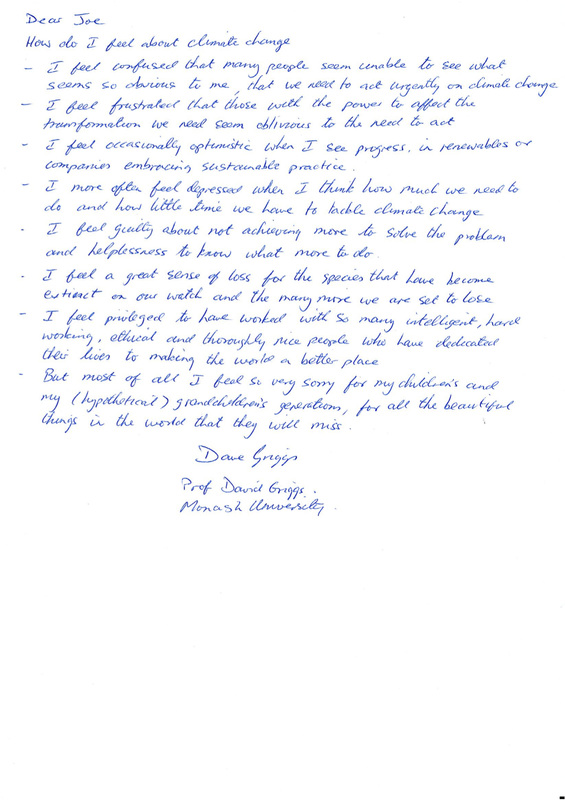

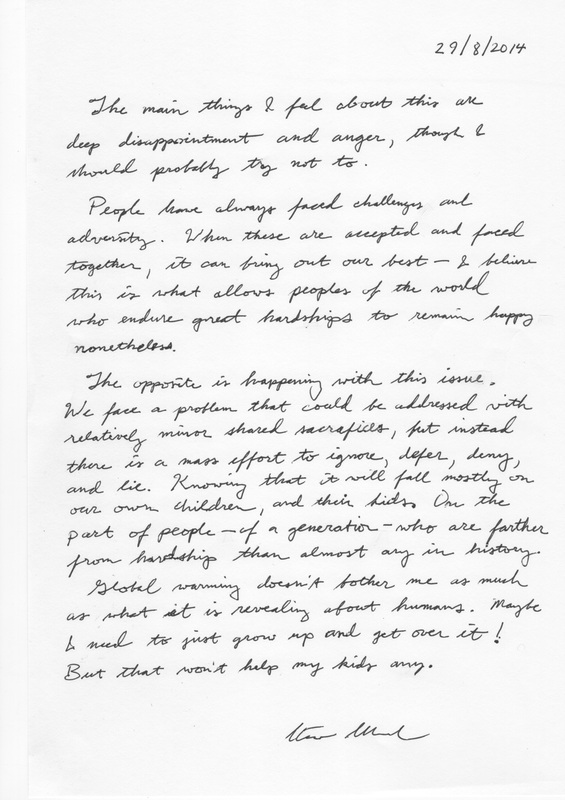

Luckily there are a large group of passionate individuals who have dedicated their lives to studying climate change. These people write complex research papers, unpacking every aspect of climate change, analysing it thoroughly and clinically. They understand the numbers, the facts and the figures. They know what is causing it, what the impacts will be and how we can minimise these impacts.

But they're not robots. These scientists are mothers, fathers, grandparents, daughters. They are real people. And they're concerned.

Luckily there are a large group of passionate individuals who have dedicated their lives to studying climate change. These people write complex research papers, unpacking every aspect of climate change, analysing it thoroughly and clinically. They understand the numbers, the facts and the figures. They know what is causing it, what the impacts will be and how we can minimise these impacts.

But they're not robots. These scientists are mothers, fathers, grandparents, daughters. They are real people. And they're concerned.

Letters written in 2020

Below are a selection of first time contributors to ITHYF

Below are a selection of first time contributors to ITHYF

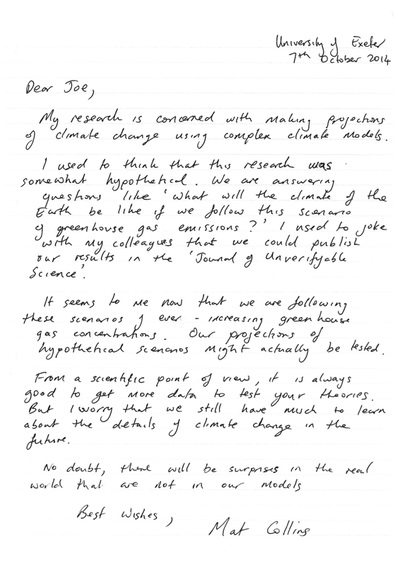

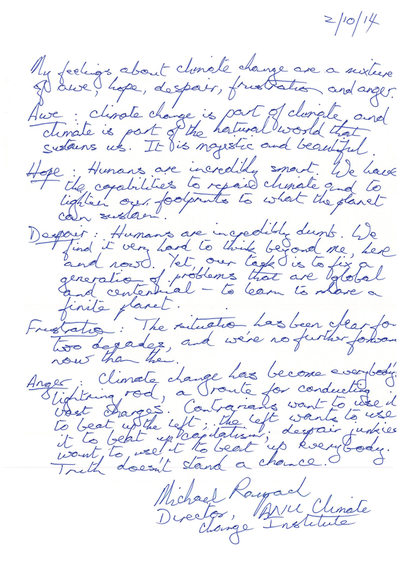

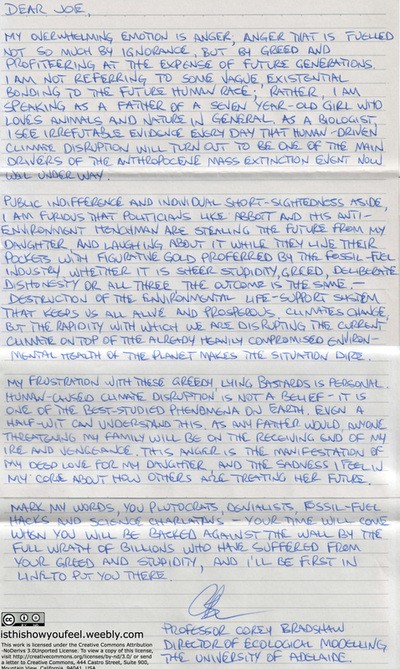

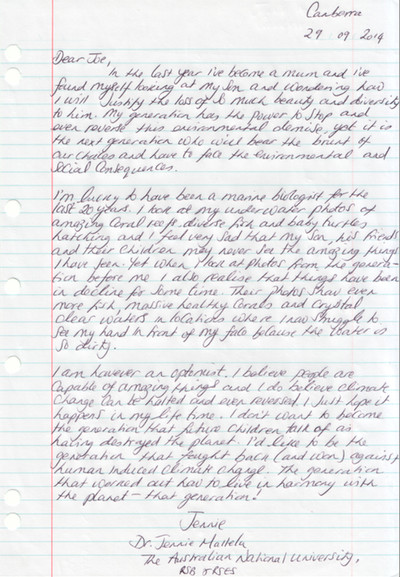

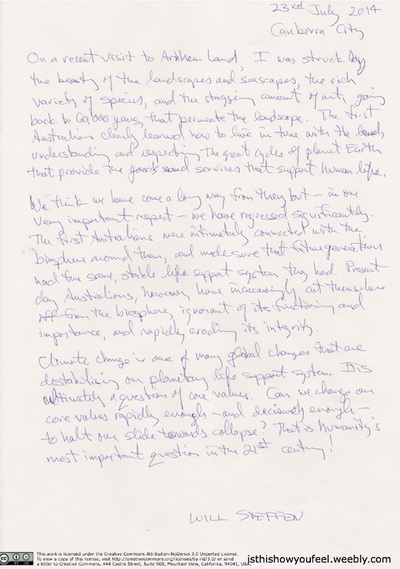

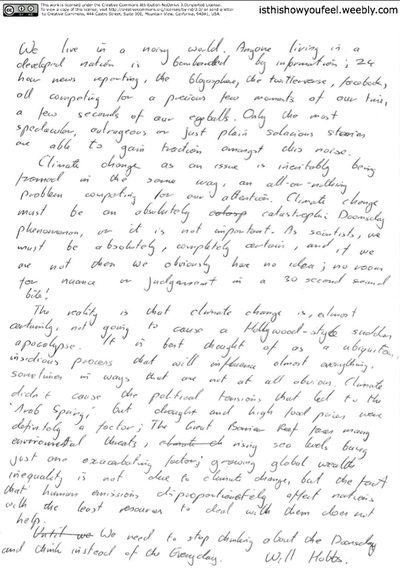

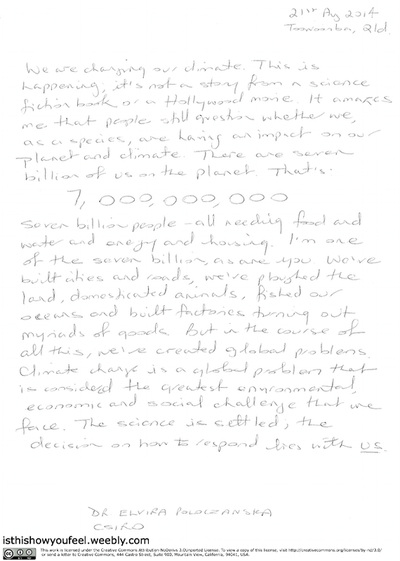

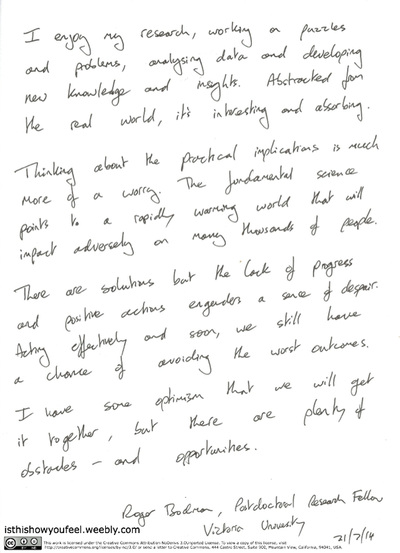

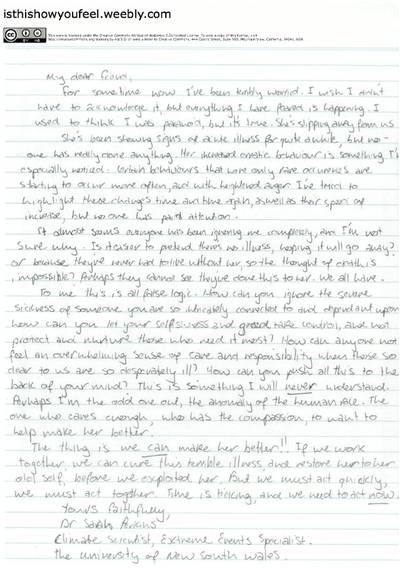

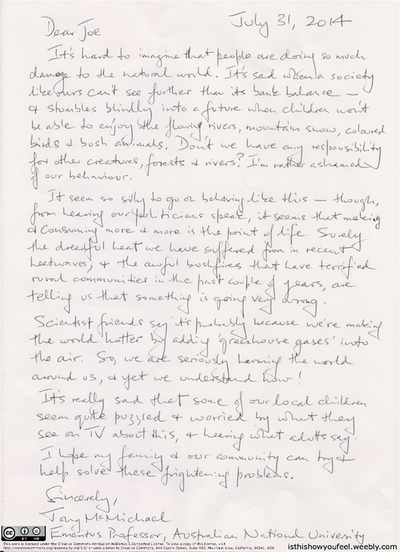

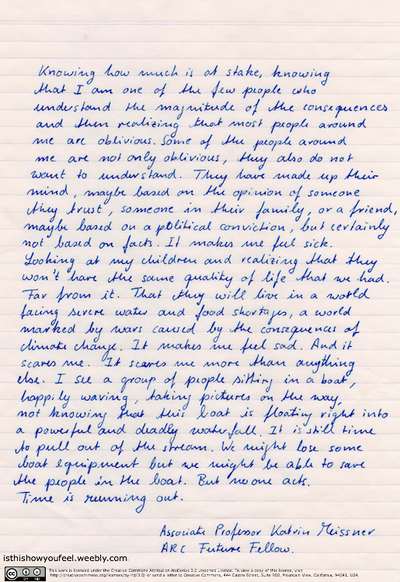

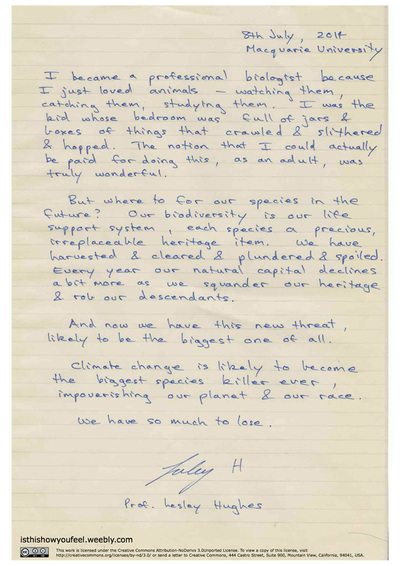

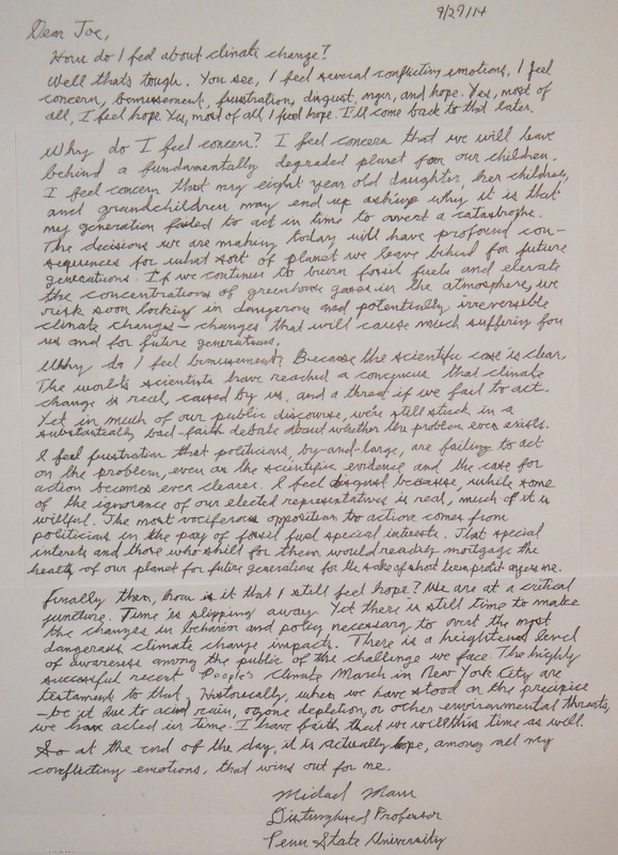

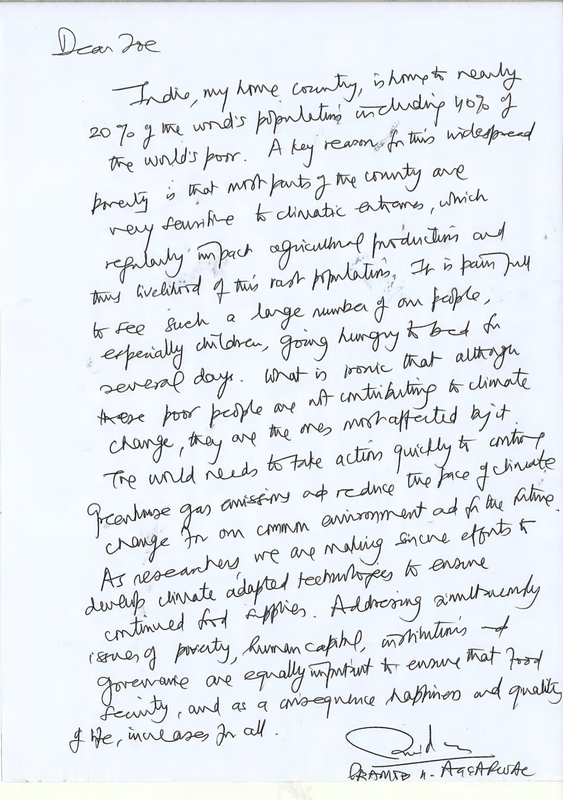

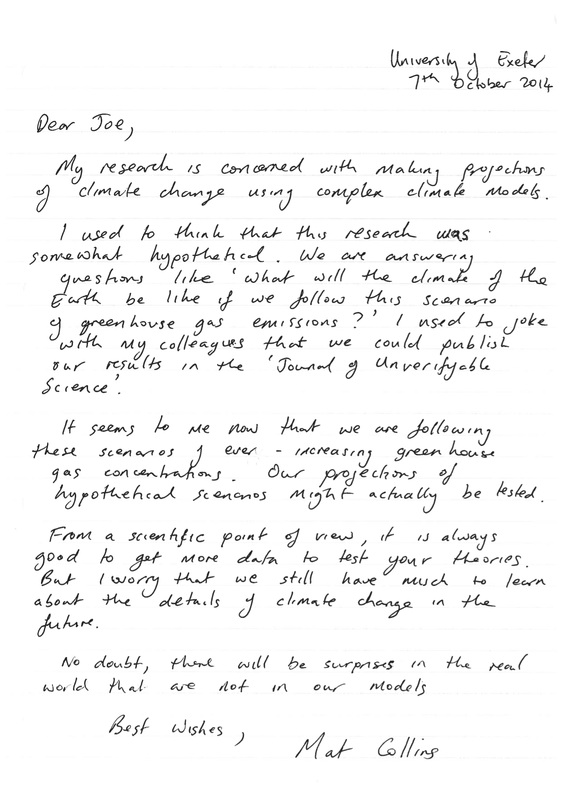

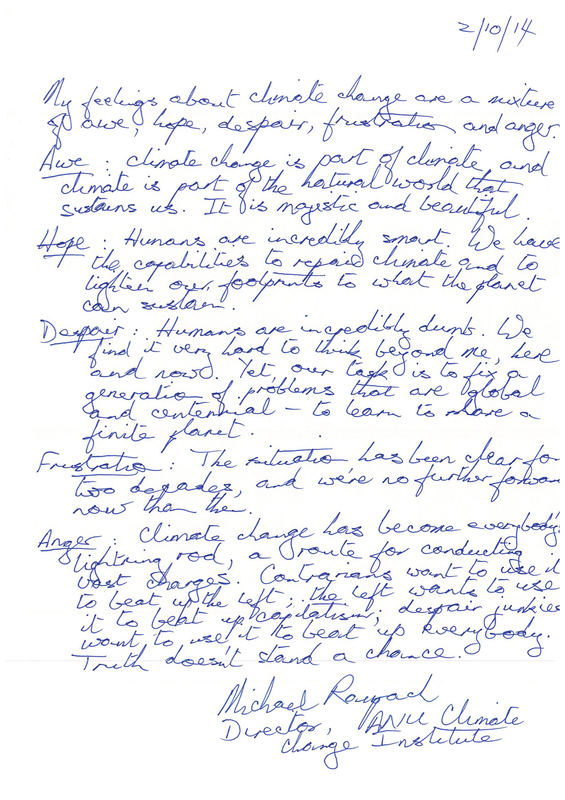

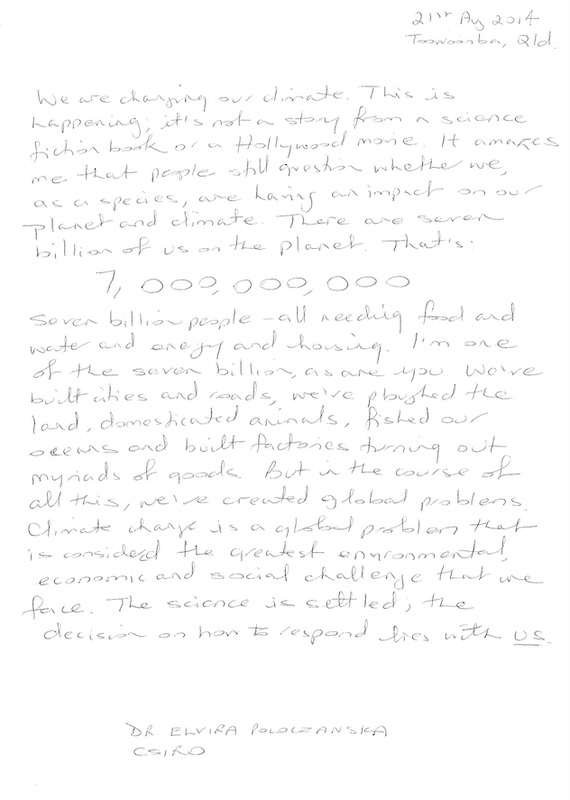

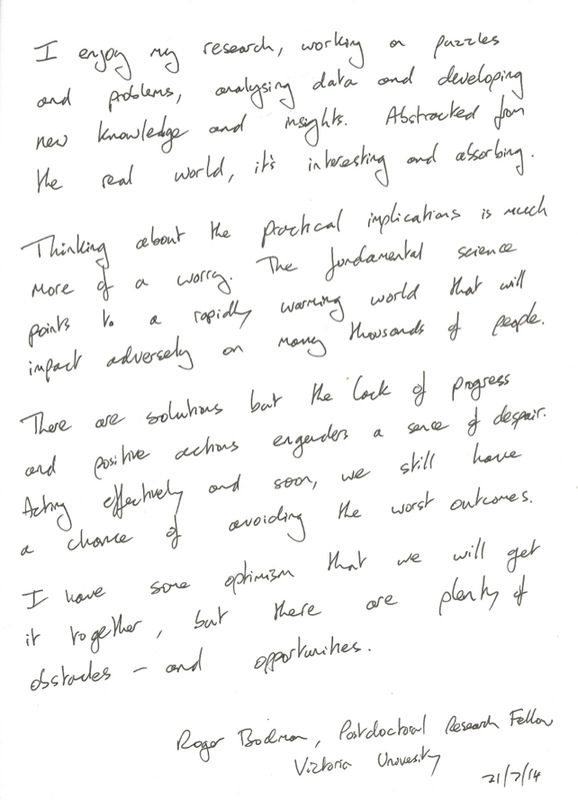

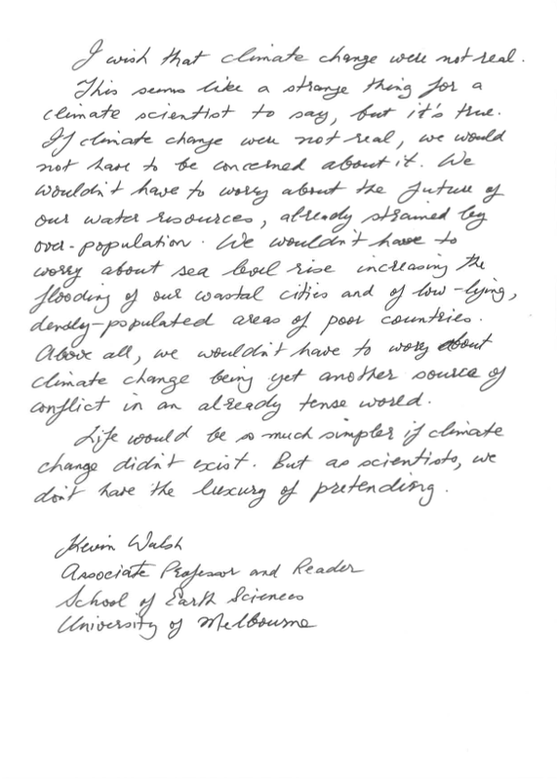

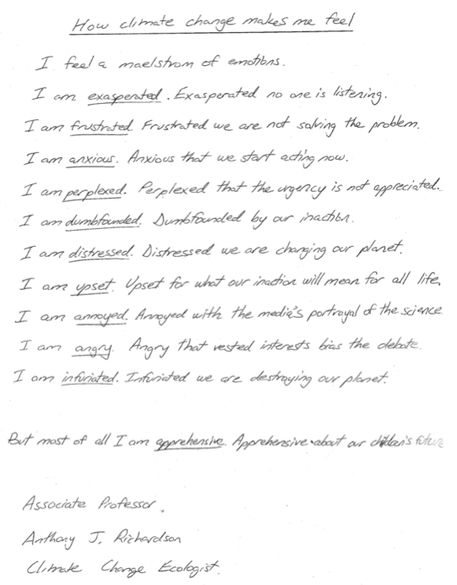

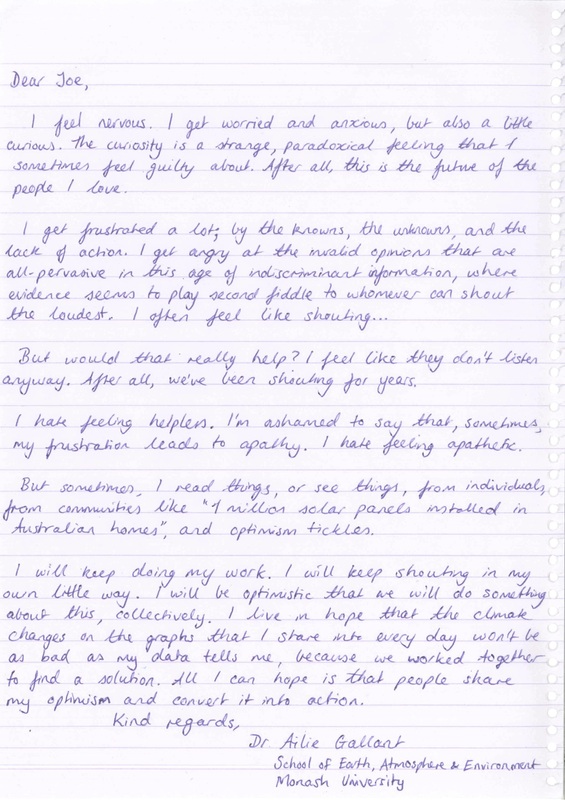

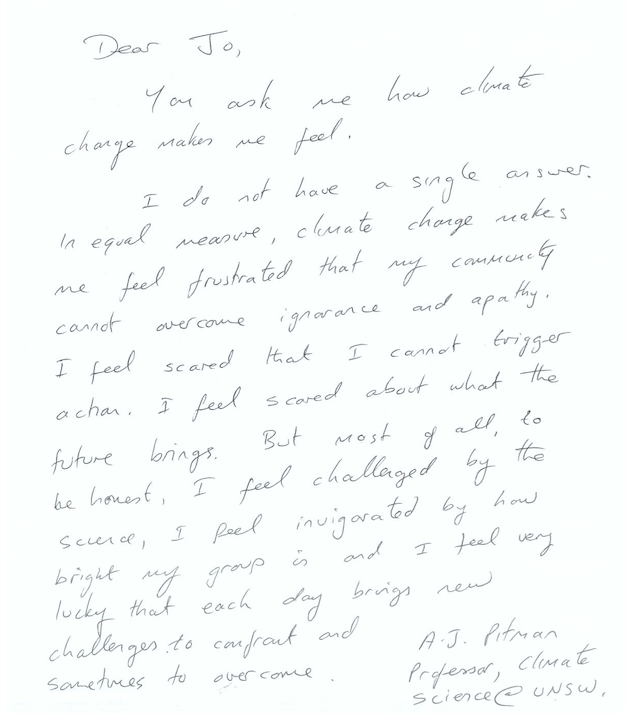

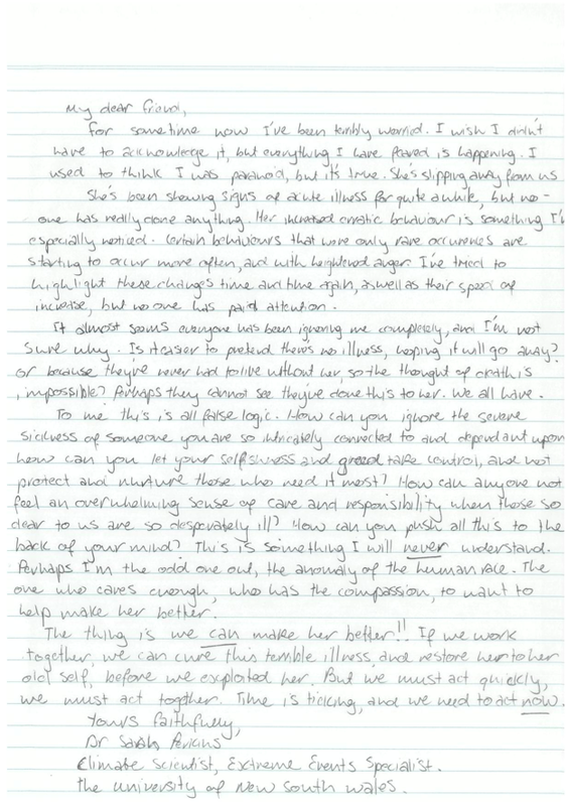

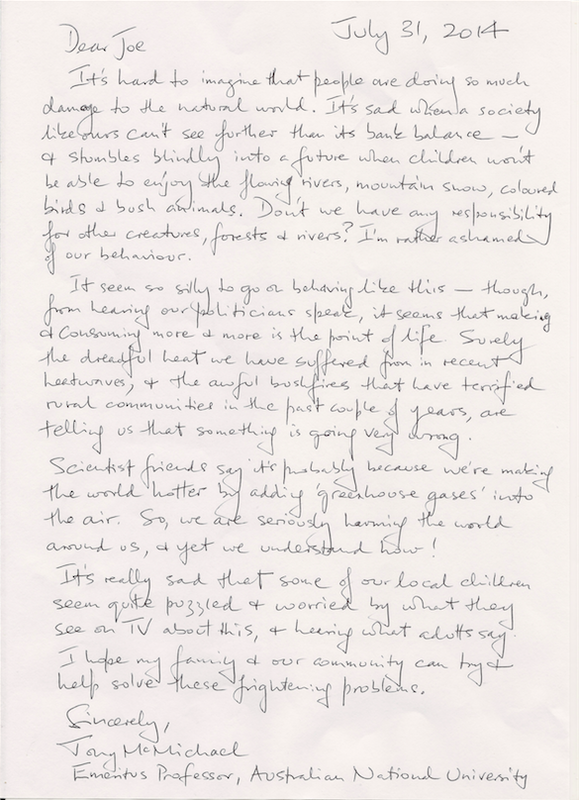

Letters written in 2014-2016

Many of these researchers have written new letters in 2020. Click here to see the collection: ITHYF5

Many of these researchers have written new letters in 2020. Click here to see the collection: ITHYF5

2020:

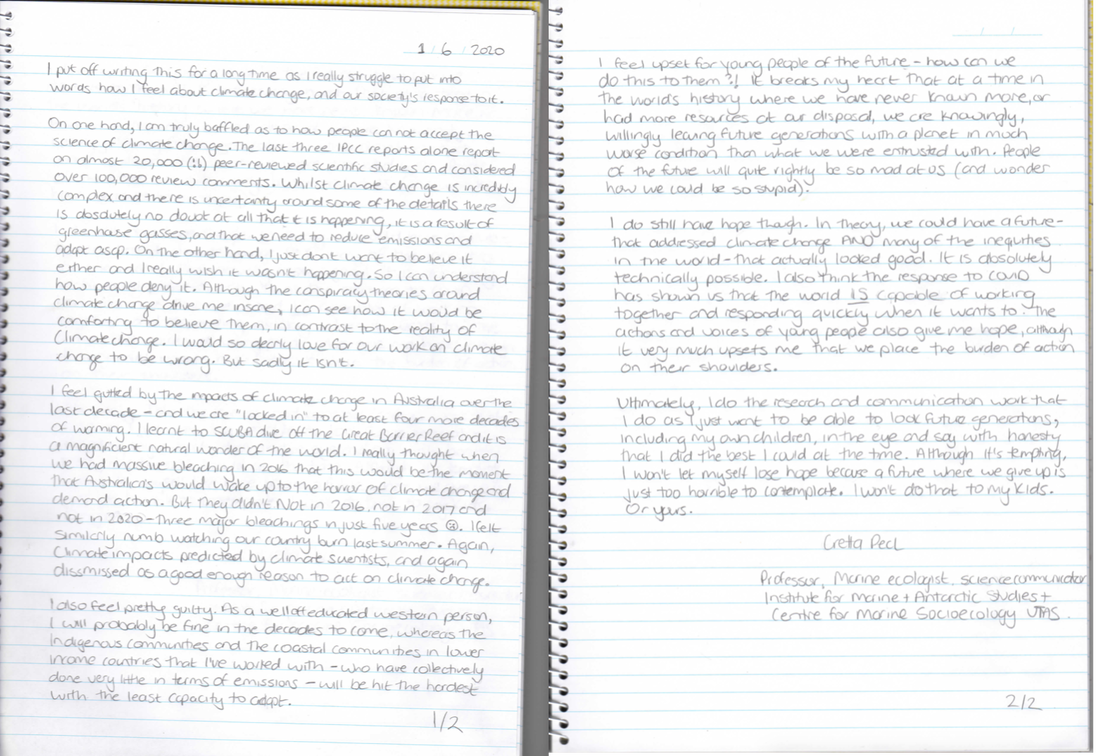

Professor Greta Pecl

Marine ecologist, science communicator

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies and Centre for Marine Socioecology UTAS

Marine ecologist, science communicator

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies and Centre for Marine Socioecology UTAS

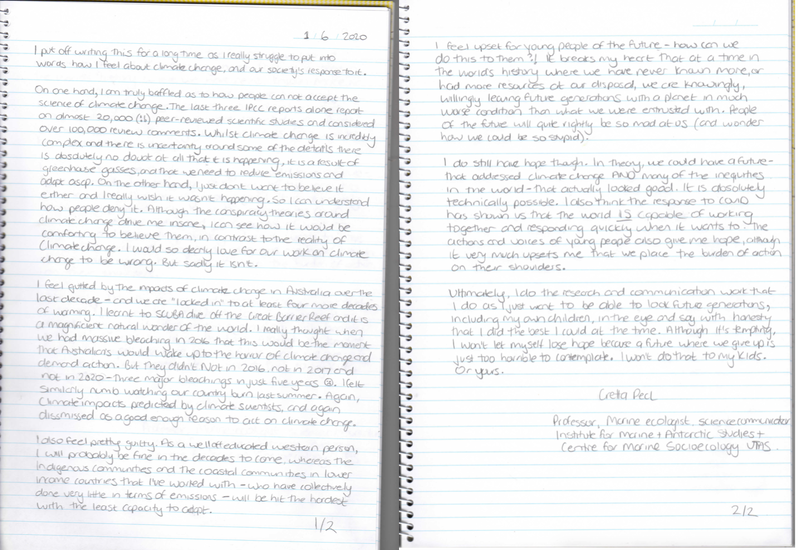

I put off writing this for a long time as I really struggle to put into words how I feel about climate change, and our society’s response to it.

On one hand, I am truly baffled as to how people can not accept the science of climate change. The last three IPCC reports alone report on almost 20,000 (!!) peer-reviewed scientific studies and considered over 100,000 review comments. Whilst climate change is incredibly complex and there is uncertainty around some of the details there is absolutely no doubt at all that it is happening, it is a result of greenhouse gasses and that we need to reduce emissions and adapt asap. On the other hand, I just don’t want to believe it either and I really wish it wasn’t happening. So I can understand how people deny it. Although the conspiracy theories around climate change drive me insane, I can see how it would be comforting to believe them, in contrast to the reality of climate change. I would so dearly love for our work on climate change to be wrong. But sadly it isn’t.

I feel gutted by the impacts of climate change in Australia over the last decade – and we are “locked in” to at least four more decades of warming. I learnt to SCUBA dive off the Great Barrier Reef and it is a magnificent natural wonder of the world. I really thought when we had massive bleaching in 2016 that this would be the moment that Australians would wake up to the horror of climate change and demand action. But they didn’t not in 2016, not in 2017 and not in 2020 – three major bleachings in just five years. I felt similarly numb watching our country burn last summer. Again, climate impacts predicted by climate scientists, and again dismissed as a food enough reason to not act on climate change.

I also feel pretty guilty. As a well off educated western person, I will probably be fine in the decades to come, whereas the indigenous communities and the coastal communities in lower income countries that I’ve worked with – who have collectively done very little in terms of emissions – will be hit the hardest with the least capacity to adapt.

I feel upset for young people of the future – how can we do this to the?! It breaks my heart that at a time in the world’s history where we have never known more, or had more resources at out disposal, we are knowingly, willingly leaving future generations with a planet in much worse condition that what we were entrusted with. People of the future will quite rightly be so mad at us (and wonder how we could be so stupid).

I do still have hope though. In theory, we could have a future – that addressed climate change AND many of the inequities in the world – that actually looked good. It is absolutely technically possible. I also think the response to COVID has shown us that the world IS capable of working together and responding quickly when it wants to. The actions and voices of young people also give me hope, although it very much upsets me that we place the burden of action on their shoulders.

Ultimately I do the research and communication work that I do as I just want to be able to look future generations, including my own children, in the eye and say with honesty that I did the best I could at the time. Although it’s tempting, I won’t let myself lose hope because a future where we give up is just too horrible to contemplate. I won’t do that to my kids. Or yours.

Gretta Pecl

Professor, Marine ecologist, science communicator

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies and Centre for Marine Socioecology UTAS

On one hand, I am truly baffled as to how people can not accept the science of climate change. The last three IPCC reports alone report on almost 20,000 (!!) peer-reviewed scientific studies and considered over 100,000 review comments. Whilst climate change is incredibly complex and there is uncertainty around some of the details there is absolutely no doubt at all that it is happening, it is a result of greenhouse gasses and that we need to reduce emissions and adapt asap. On the other hand, I just don’t want to believe it either and I really wish it wasn’t happening. So I can understand how people deny it. Although the conspiracy theories around climate change drive me insane, I can see how it would be comforting to believe them, in contrast to the reality of climate change. I would so dearly love for our work on climate change to be wrong. But sadly it isn’t.

I feel gutted by the impacts of climate change in Australia over the last decade – and we are “locked in” to at least four more decades of warming. I learnt to SCUBA dive off the Great Barrier Reef and it is a magnificent natural wonder of the world. I really thought when we had massive bleaching in 2016 that this would be the moment that Australians would wake up to the horror of climate change and demand action. But they didn’t not in 2016, not in 2017 and not in 2020 – three major bleachings in just five years. I felt similarly numb watching our country burn last summer. Again, climate impacts predicted by climate scientists, and again dismissed as a food enough reason to not act on climate change.

I also feel pretty guilty. As a well off educated western person, I will probably be fine in the decades to come, whereas the indigenous communities and the coastal communities in lower income countries that I’ve worked with – who have collectively done very little in terms of emissions – will be hit the hardest with the least capacity to adapt.

I feel upset for young people of the future – how can we do this to the?! It breaks my heart that at a time in the world’s history where we have never known more, or had more resources at out disposal, we are knowingly, willingly leaving future generations with a planet in much worse condition that what we were entrusted with. People of the future will quite rightly be so mad at us (and wonder how we could be so stupid).

I do still have hope though. In theory, we could have a future – that addressed climate change AND many of the inequities in the world – that actually looked good. It is absolutely technically possible. I also think the response to COVID has shown us that the world IS capable of working together and responding quickly when it wants to. The actions and voices of young people also give me hope, although it very much upsets me that we place the burden of action on their shoulders.

Ultimately I do the research and communication work that I do as I just want to be able to look future generations, including my own children, in the eye and say with honesty that I did the best I could at the time. Although it’s tempting, I won’t let myself lose hope because a future where we give up is just too horrible to contemplate. I won’t do that to my kids. Or yours.

Gretta Pecl

Professor, Marine ecologist, science communicator

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies and Centre for Marine Socioecology UTAS

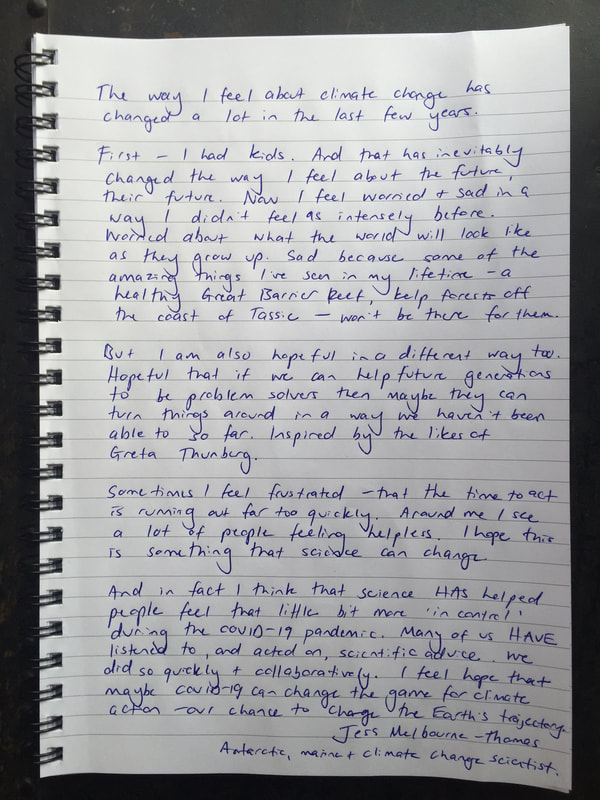

Dr Jess Melbourne-Thomas

Transdisciplinary Researcher & Knowledge Broker

Oceans & Atmosphere, CSIRO

Transdisciplinary Researcher & Knowledge Broker

Oceans & Atmosphere, CSIRO

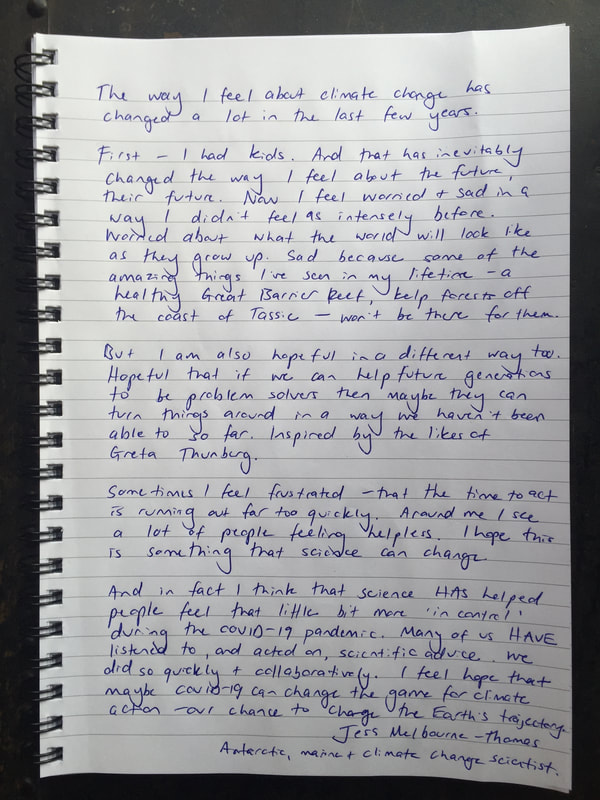

The way I feel about climate change has changed a lot in the last few years.

First – I had kids. And that has inevitably changed the way I feel about the future, their future. Now I feel worried and sad in a way I didn’t feel as intensely before. Worried about what the world will look like as they grow up. Sad because some of the amazing things I’ve seen in my lifetime – a healthy Great Barrier Reef, kelp forests off the coast of Tassie – won’t be there for them.

But I am also hopeful in a different way too. Hopeful that if we can help future generations to be problem solvers then maybe they can turn things around in a way we haven’t been able to so far. Inspired by the likes of Greta Thunberg.

Sometimes I feel frustrated – that the time to act is running out far too quickly. Around me I see a lot of people feeling helpless. I hope this is something that science can change.

And in fact I think that science HAS helped people feel that little bit more ‘in-control’ during COVID-19 pandemic. Many of us HAVE listened to, and acted on, scientific advice. We did so quickly and collaboratively. I feel hope that maybe COVID-19 can change the game for climate action – our chance to change the Earth’s trajectory.

Jess Melbourne – Thomas

Antarctic, marine and climate change scientist.

First – I had kids. And that has inevitably changed the way I feel about the future, their future. Now I feel worried and sad in a way I didn’t feel as intensely before. Worried about what the world will look like as they grow up. Sad because some of the amazing things I’ve seen in my lifetime – a healthy Great Barrier Reef, kelp forests off the coast of Tassie – won’t be there for them.

But I am also hopeful in a different way too. Hopeful that if we can help future generations to be problem solvers then maybe they can turn things around in a way we haven’t been able to so far. Inspired by the likes of Greta Thunberg.

Sometimes I feel frustrated – that the time to act is running out far too quickly. Around me I see a lot of people feeling helpless. I hope this is something that science can change.

And in fact I think that science HAS helped people feel that little bit more ‘in-control’ during COVID-19 pandemic. Many of us HAVE listened to, and acted on, scientific advice. We did so quickly and collaboratively. I feel hope that maybe COVID-19 can change the game for climate action – our chance to change the Earth’s trajectory.

Jess Melbourne – Thomas

Antarctic, marine and climate change scientist.

Dr Linden Ashcroft

Climate Researcher and Lecturer

University of Melbourne

Climate Researcher and Lecturer

University of Melbourne

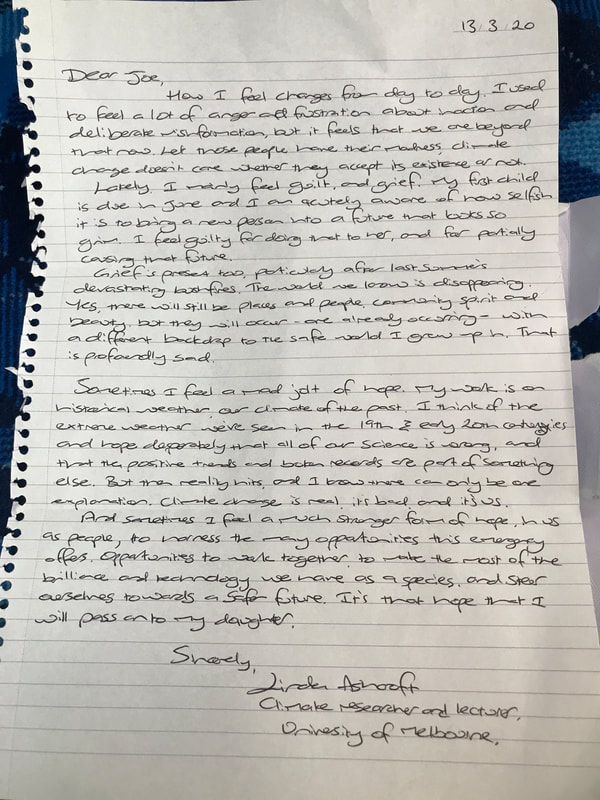

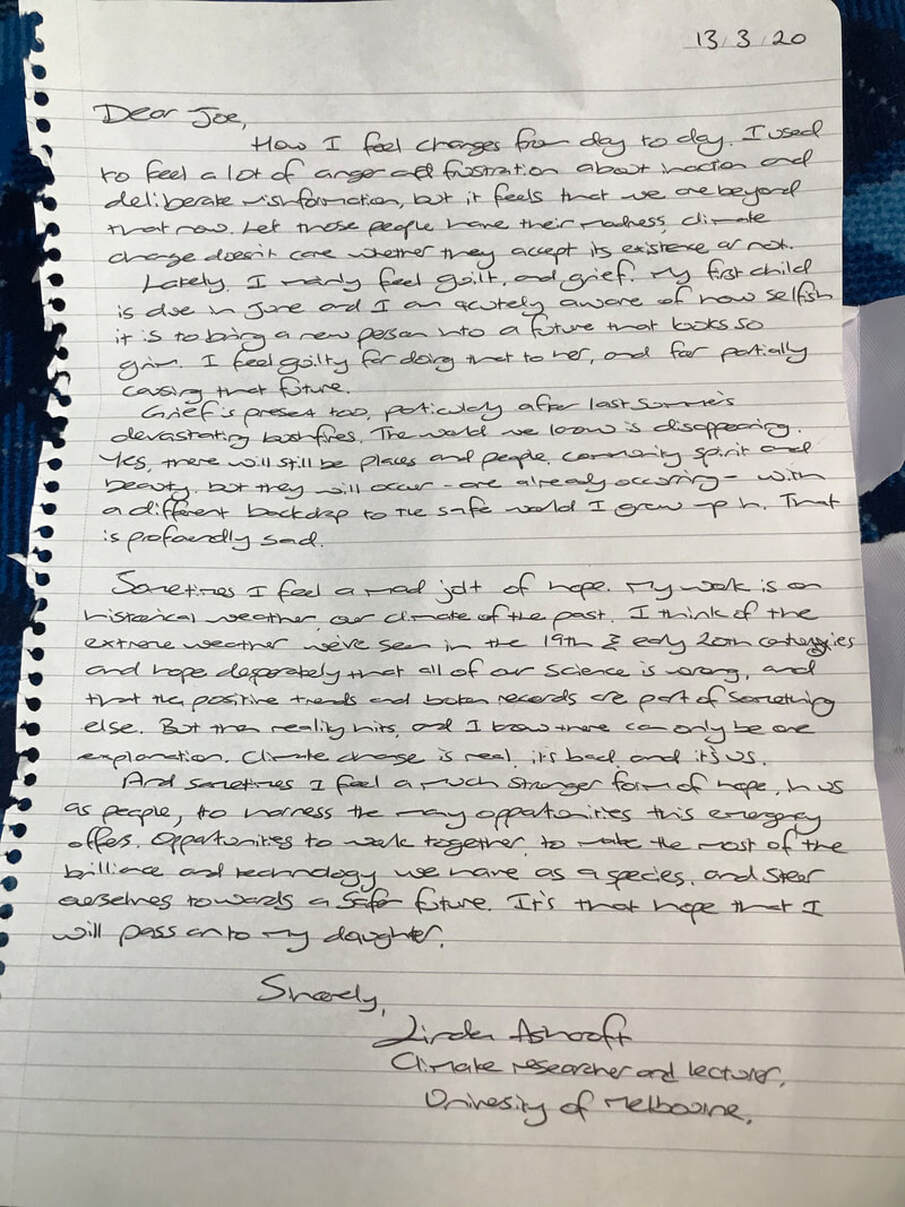

Dear Joe,

How I feel changes from day to day. I used to feel a lot of anger and frustration about inaction and deliberate misinformation, but it feels that we are beyond that now. Let these people have their madness, climate change doesn’t care whether they accept its existence or not.

Lately I mainly feel guilt, and grief. My first child is due in June and I am acutely aware of how selfish it is to bring a new person into a future that looks so grim. I feel guilty for doing that to her, and for partially causing that future.

Grief is present too, particularly after last summer’s devastating bushfires. The world we know is disappearing. Yes, there will still be places and people, community spirit and beauty, but they will occur - are already occurring - with a different backdrop to the safe world I grew up in. That is profoundly sad.

Sometimes I feel a mad jolt of hope. My work is on historical weather, our climate of the past. I think of the extreme weather we’ve seen in the 19th and early 20th centuries and hope desperately that the positive trends and broken records are part of something else. But then reality hits, and I know there can only be one explanation. Climate change is real, it’s bad and it’s us.

And sometimes I feel a much stronger form of hope, in us as people, to harness the many opportunities to work together, to make the most of the brilliance and technology we have as a species, and steer ourselves towards a safer future. It’s that hope that I will pass onto my daughter.

Sincerely,

Linden Ashcroft

Climate researcher and lecturer,

University of Melbourne

How I feel changes from day to day. I used to feel a lot of anger and frustration about inaction and deliberate misinformation, but it feels that we are beyond that now. Let these people have their madness, climate change doesn’t care whether they accept its existence or not.

Lately I mainly feel guilt, and grief. My first child is due in June and I am acutely aware of how selfish it is to bring a new person into a future that looks so grim. I feel guilty for doing that to her, and for partially causing that future.

Grief is present too, particularly after last summer’s devastating bushfires. The world we know is disappearing. Yes, there will still be places and people, community spirit and beauty, but they will occur - are already occurring - with a different backdrop to the safe world I grew up in. That is profoundly sad.

Sometimes I feel a mad jolt of hope. My work is on historical weather, our climate of the past. I think of the extreme weather we’ve seen in the 19th and early 20th centuries and hope desperately that the positive trends and broken records are part of something else. But then reality hits, and I know there can only be one explanation. Climate change is real, it’s bad and it’s us.

And sometimes I feel a much stronger form of hope, in us as people, to harness the many opportunities to work together, to make the most of the brilliance and technology we have as a species, and steer ourselves towards a safer future. It’s that hope that I will pass onto my daughter.

Sincerely,

Linden Ashcroft

Climate researcher and lecturer,

University of Melbourne

Professor Johan Rockström

Director, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

Director, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

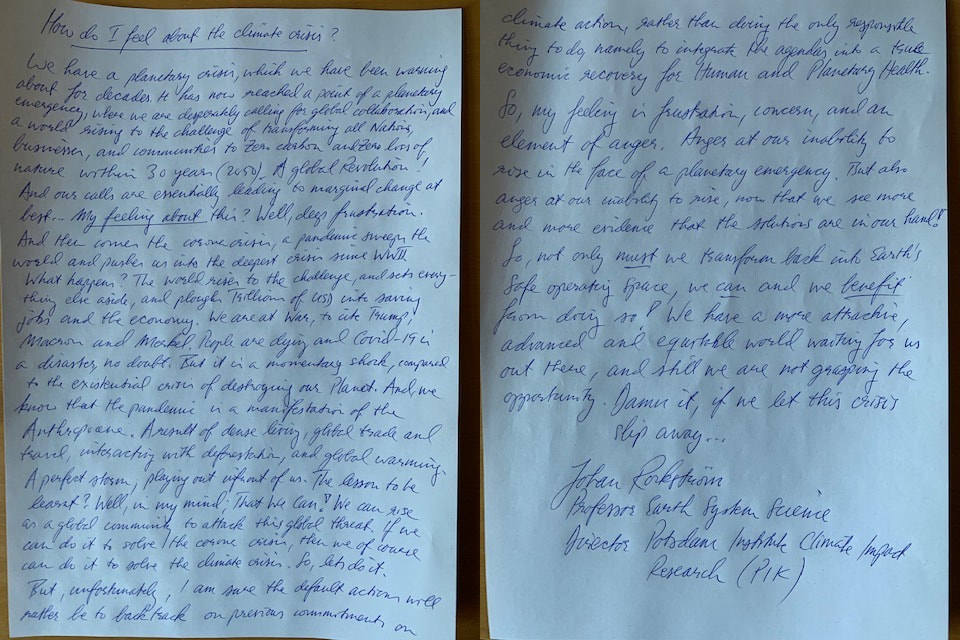

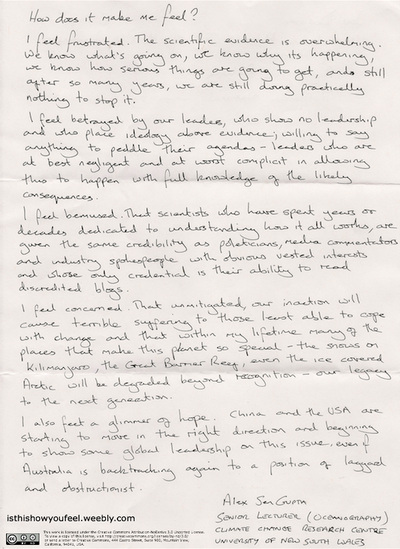

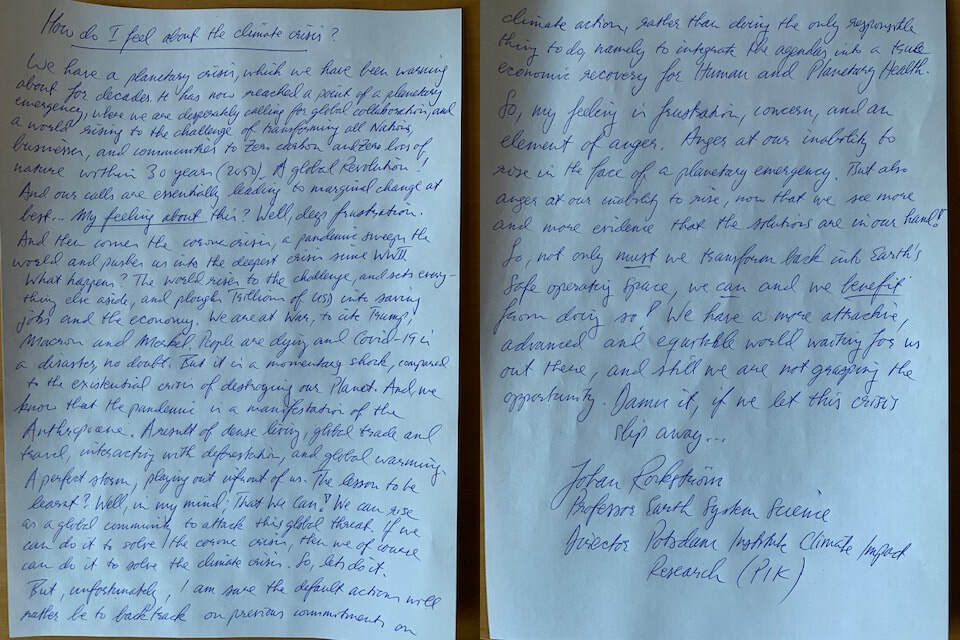

How do I feel about the climate crisis?

We have a planetary crisis, which we have been warning about for decades. It has now reached a point of planetary emergency, where we are desperately calling for global collaboration. and a world rising to the challenge of transforming all Nations, businesses and communities to zero carbon and zero loss of nature within 30 years (2050). A global Revolution! And our calls are essentially leading to marginal change at best... My feeling about this? Well, deep frustration.

And then comes the corona crisis, a pandemic sweeps the world and pushes us into the deepest crisis since WWII. What happensL The world rises to the challenge , and sets everything else aside, and ploughs trillions of USD into saving jobs and the economy. We are at War, to cite Trump, Macron and Merkel. People are dying and Covid-19 is a disaster, no doubt. But it is a momentary shock, compared to the existential crisis of destroying our planet. And we know that the pandemic is a manifestation of the Anthropocene. A result of dense living, global trade and travel, interacting with deforestation and global warming.

A perfect storm, playing out in front of us. The lesson to be learnt? Well, in my mind; That we can! We can rise as a global community to attack this global threat. If we can do it to solve the corona crisis, then we of course can do it to solve the climate crisis. So, let's do it.

But, unfortunately, I am sure the default action will rather be to backtrack on previous commitments on climate action, rather than doing the only responsible thing to do, namely to integrate the agendas into a true economic recovery for Human and Planetary Health.

So, my feeling is frustration, concern and an element of anger. Anger at our inability to rise in the face of a planetary emergency. But also anger at our inability to rise, now that we see more and more evidence that the solutions are in our hand!

So, not only must we transform back into Earth's safe operating space, we can and we benefit from doing so! We have a more attractive, advanced and equitable world waiting for us out there, and still we are not grasping the opportunity.

Damn it, if we let this crisis slip away...

Johan Rockström

Professor Earth System Science

Director Potsdam Institute Climate Impact Research (PIK)

We have a planetary crisis, which we have been warning about for decades. It has now reached a point of planetary emergency, where we are desperately calling for global collaboration. and a world rising to the challenge of transforming all Nations, businesses and communities to zero carbon and zero loss of nature within 30 years (2050). A global Revolution! And our calls are essentially leading to marginal change at best... My feeling about this? Well, deep frustration.

And then comes the corona crisis, a pandemic sweeps the world and pushes us into the deepest crisis since WWII. What happensL The world rises to the challenge , and sets everything else aside, and ploughs trillions of USD into saving jobs and the economy. We are at War, to cite Trump, Macron and Merkel. People are dying and Covid-19 is a disaster, no doubt. But it is a momentary shock, compared to the existential crisis of destroying our planet. And we know that the pandemic is a manifestation of the Anthropocene. A result of dense living, global trade and travel, interacting with deforestation and global warming.

A perfect storm, playing out in front of us. The lesson to be learnt? Well, in my mind; That we can! We can rise as a global community to attack this global threat. If we can do it to solve the corona crisis, then we of course can do it to solve the climate crisis. So, let's do it.

But, unfortunately, I am sure the default action will rather be to backtrack on previous commitments on climate action, rather than doing the only responsible thing to do, namely to integrate the agendas into a true economic recovery for Human and Planetary Health.

So, my feeling is frustration, concern and an element of anger. Anger at our inability to rise in the face of a planetary emergency. But also anger at our inability to rise, now that we see more and more evidence that the solutions are in our hand!

So, not only must we transform back into Earth's safe operating space, we can and we benefit from doing so! We have a more attractive, advanced and equitable world waiting for us out there, and still we are not grasping the opportunity.

Damn it, if we let this crisis slip away...

Johan Rockström

Professor Earth System Science

Director Potsdam Institute Climate Impact Research (PIK)

Dr Ariaan Purich

Research Associate, Climate Change Research Centre

University of New South Wales

Research Associate, Climate Change Research Centre

University of New South Wales

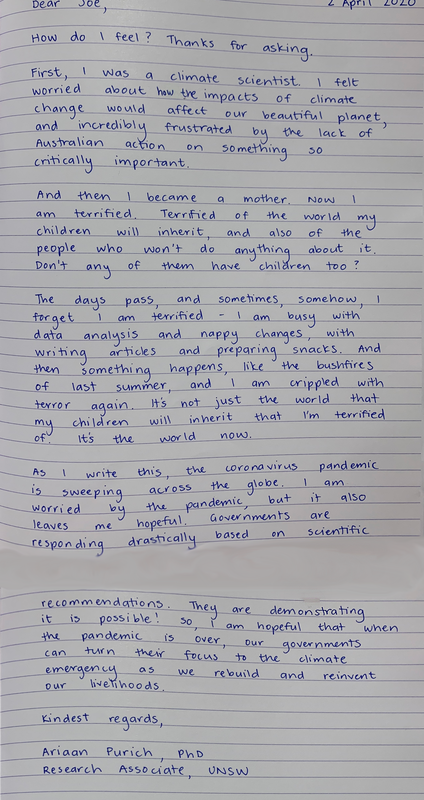

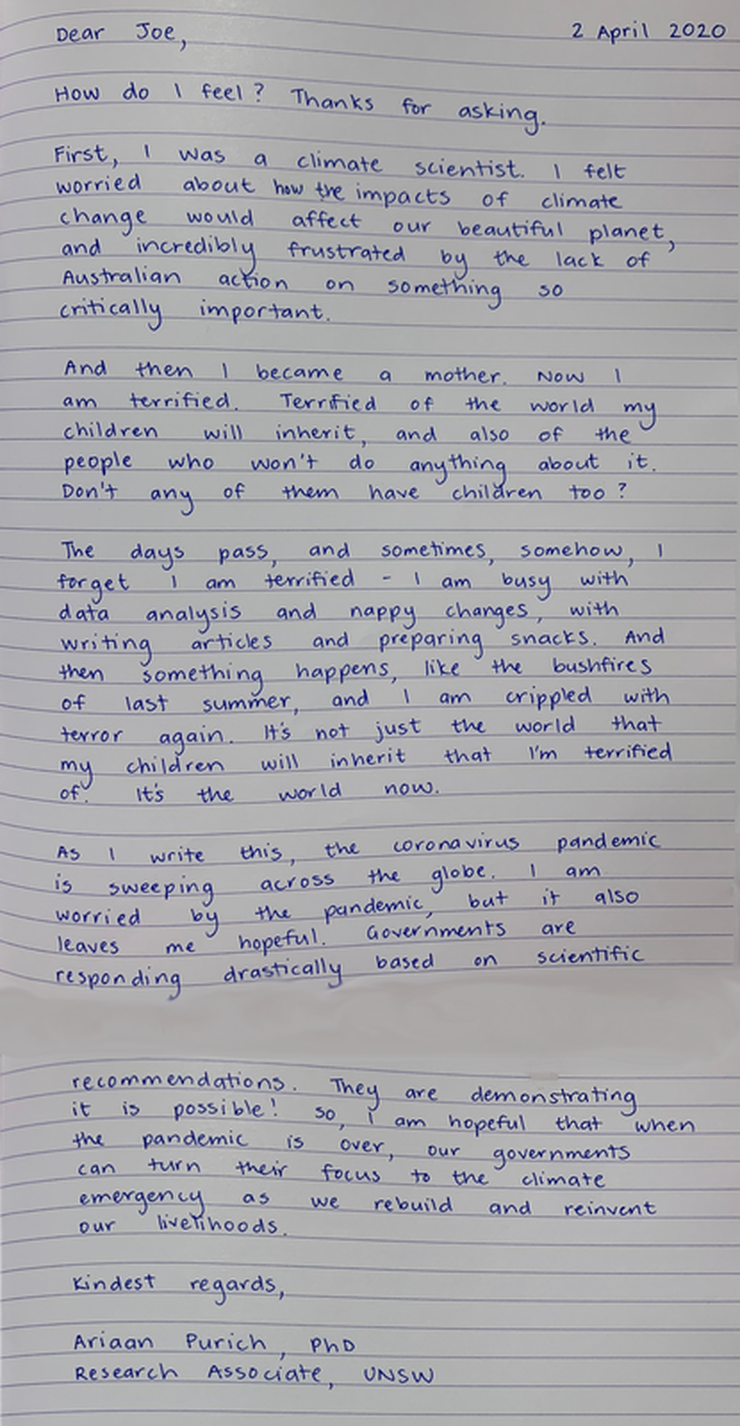

Dear Joe,

How do I feel? Thanks for asking.

First, I was a climate scientist. I felt worried about how the impacts of climate change would affect our beautiful planet, and incredibly frustrated by the lack of Australian action on something so critically important.

And then I become a mother. Now I am terrified. Terrified of the world my children will inherit, and also of the people who won’t do anything about it. Don’t any of them have children too?

The days pass, and sometimes, somehow, I forget I am terrified – I am busy with data analysis and nappy changes, with writing articles and preparing snacks. And then something happens, like the bushfires of last summer, and I am crippled with terror again. It’s not just the world that my children will inherit that I’m terrified of. It’s the world now.

As I write this, the coronavirus pandemic is sweeping across the globe. I am worried by the pandemic, but it also leaves me hopeful. Governments are responding drastically based on scientific recommendations. They are demonstrating it is possible! So, I am hopeful that when the pandemic is over, our governments can turn their focus to the climate emergency as we rebuild and reinvent our livelihoods.

Kindest regards,

Ariaan Purich, PhD

Research Associate, UNSW

How do I feel? Thanks for asking.

First, I was a climate scientist. I felt worried about how the impacts of climate change would affect our beautiful planet, and incredibly frustrated by the lack of Australian action on something so critically important.

And then I become a mother. Now I am terrified. Terrified of the world my children will inherit, and also of the people who won’t do anything about it. Don’t any of them have children too?

The days pass, and sometimes, somehow, I forget I am terrified – I am busy with data analysis and nappy changes, with writing articles and preparing snacks. And then something happens, like the bushfires of last summer, and I am crippled with terror again. It’s not just the world that my children will inherit that I’m terrified of. It’s the world now.

As I write this, the coronavirus pandemic is sweeping across the globe. I am worried by the pandemic, but it also leaves me hopeful. Governments are responding drastically based on scientific recommendations. They are demonstrating it is possible! So, I am hopeful that when the pandemic is over, our governments can turn their focus to the climate emergency as we rebuild and reinvent our livelihoods.

Kindest regards,

Ariaan Purich, PhD

Research Associate, UNSW

Dr Joanne S. Johnson,

British Antarctic Survey

British Antarctic Survey

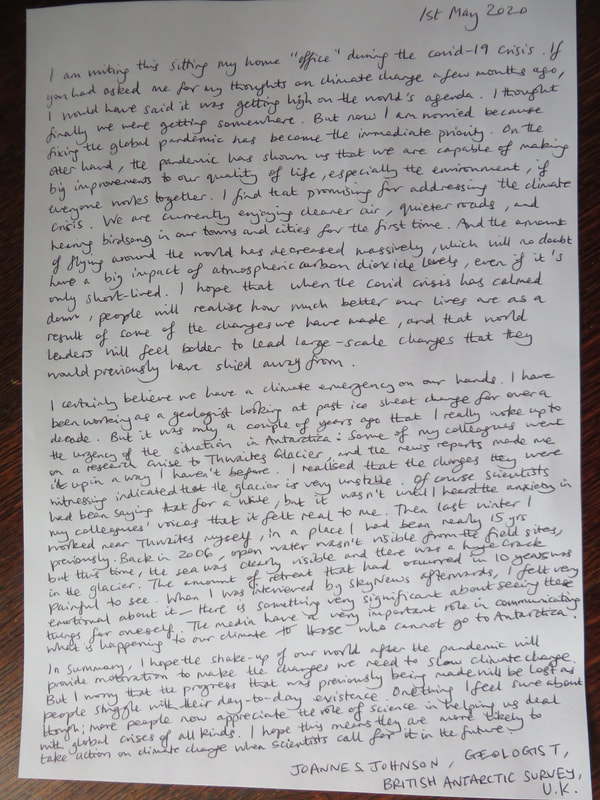

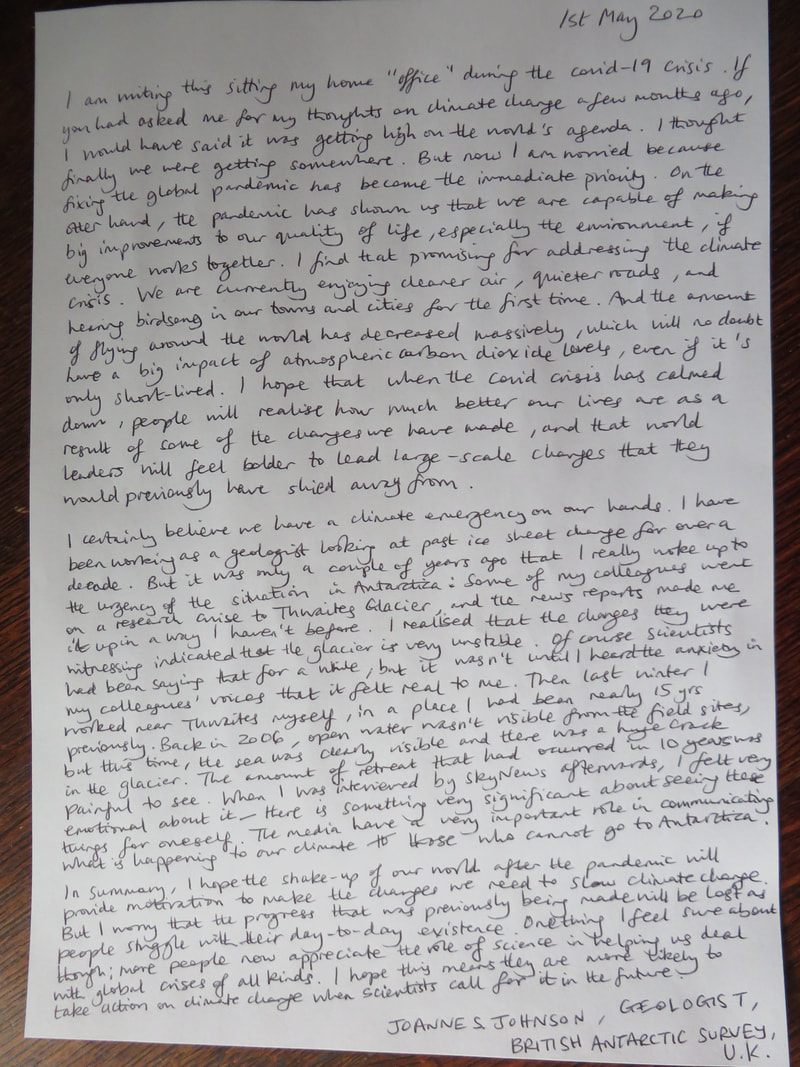

I am writing this sitting (in) my home “office: during the covid-19 crisis. If you had asked me for my thoughts on climate change a few months ago, I would have said it was getting high on the world’s agenda. I thought finally we were getting somewhere. But now I am worried because fixing the global pandemic has become the immediate priority. On the other hand, the pandemic has shown us that we are capable of making big improvements to our quality of life, especially the environment, if everyone works together. I find that promising for addressing the climate crisis. We are currently enjoying cleaner air, quieter roads, and hearing birdsong in our towns and cities for the first time. And the amount of flying around the world has decreased massively, which will no doubt have a big impact (on) carbon dioxide levels, even if it’s only short-lived. I hope that when the covid crisis has calmed down, people will realise how much better our lives are as a result of some of the changes we have made, and that world leaders will feel bolder to lead large-scale changes that they would previously have shied away from.

I certainly believe we have a climate emergency on our hands. I have been working as a geologist looking at past ice sheet change for over a decade. But is was only a couple of years ago that I really woke up to the urgency of the situation in Antarctica some of my colleagues went on a research cruise to Thwaites Glacier and the news reports made me sit up in a way I haven’t before. I realised that the changes they were witnessing indicated that the glacier is very unstable. Of course scientists had been saying that for a while, but it wasn’t until I heard the anxiety in my colleagues; voices that it felt real to me. Then last winter I worked near Thwaites myself, in a place I had been nearly 15 years previously. Back in 2006, open water wasn’t visible from the field sites, but this time, the sea was clearly visible and there was a huge crack in the glacier. The amount of retreat that had occurred in 10 years was painful to see. When I was interviewed by Sky News afterwards, I felt very emotional about it- there is something very significant about seeing these things for oneself. The media have a very important role in communicating what is happening to our climate to those who cannot go to Antarctica.

In summary, I hope the shake-up of our world after the pandemic will provide motivation to make the changes we need to slow climate change. But I worry that the progress that was previously being made will be lost as people struggle with their day-to-day existence. One thing I feel sure about though; more people now appreciate the role of science in helping us deal with global crises of all kinds. I hope this means they are more likely to take action on climate change when scientists call for it in the future.

Dr Joanne S. Johnson, Geologist,

British Antarctic Survey,

U.K.

I certainly believe we have a climate emergency on our hands. I have been working as a geologist looking at past ice sheet change for over a decade. But is was only a couple of years ago that I really woke up to the urgency of the situation in Antarctica some of my colleagues went on a research cruise to Thwaites Glacier and the news reports made me sit up in a way I haven’t before. I realised that the changes they were witnessing indicated that the glacier is very unstable. Of course scientists had been saying that for a while, but it wasn’t until I heard the anxiety in my colleagues; voices that it felt real to me. Then last winter I worked near Thwaites myself, in a place I had been nearly 15 years previously. Back in 2006, open water wasn’t visible from the field sites, but this time, the sea was clearly visible and there was a huge crack in the glacier. The amount of retreat that had occurred in 10 years was painful to see. When I was interviewed by Sky News afterwards, I felt very emotional about it- there is something very significant about seeing these things for oneself. The media have a very important role in communicating what is happening to our climate to those who cannot go to Antarctica.

In summary, I hope the shake-up of our world after the pandemic will provide motivation to make the changes we need to slow climate change. But I worry that the progress that was previously being made will be lost as people struggle with their day-to-day existence. One thing I feel sure about though; more people now appreciate the role of science in helping us deal with global crises of all kinds. I hope this means they are more likely to take action on climate change when scientists call for it in the future.

Dr Joanne S. Johnson, Geologist,

British Antarctic Survey,

U.K.

2014-2016:

Dr Lindsey Nicholson

Glaciological group leader

University of Innsbruck, Austria

Glaciological group leader

University of Innsbruck, Austria

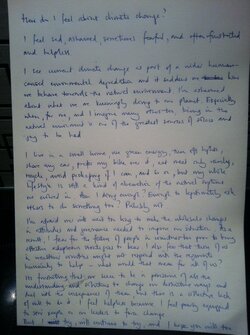

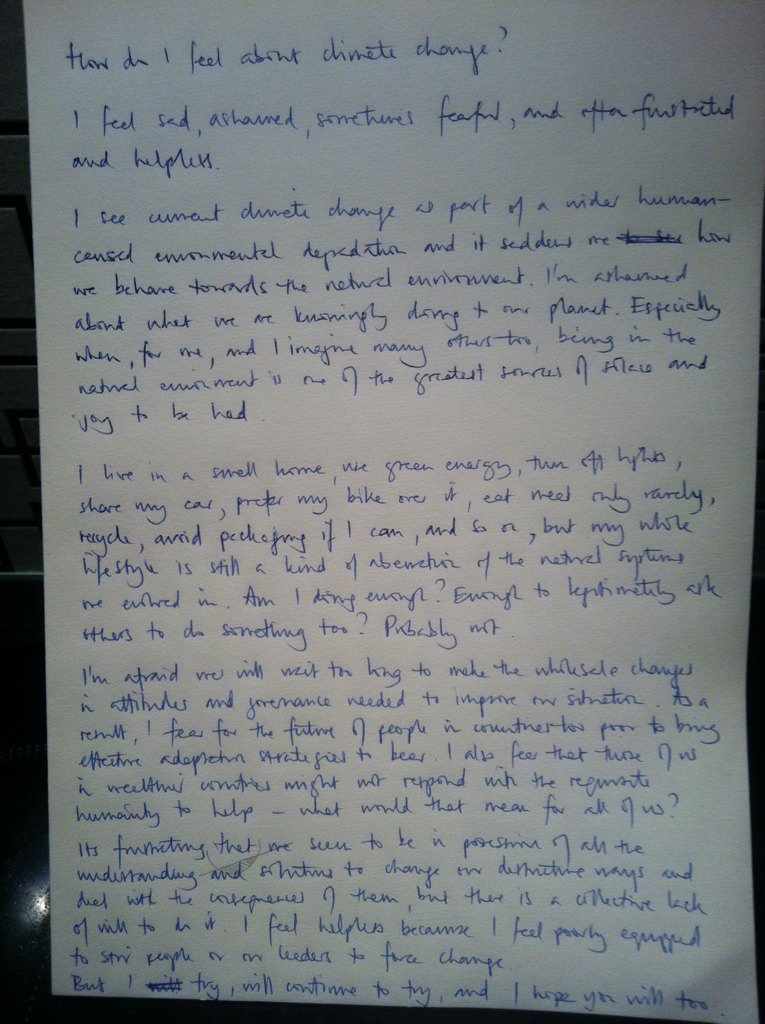

How do I feel about climate change?

I feel sad, ashamed, fearful, and often frustrated and helpless.

I see current climate change as part of a wider human caused environmental depreciation and it saddens me how we behave towards the natural environment. I’m ashamed about what we are knowingly doing to our planet. Especially when, for me, and I imagine many others, being in the natural environment is one of the greatest sources of solace and joy to be had.

I live in a small home, use green energy, turn off the lights, share my car and prefer my bike over it, eat meat only rarely, avoid packaging if I can, and so on. But my whole lifestyle is still a kind of aberration of the natural systems we evolved in. Am I doing enough? Enough to legitimately ask others to do something too? Probably not.

I’m afraid we will wait too long to make the wholesale changes in attitudes and governance needed to improve our situation. As a result, I fear for the future of people in countries too poor to bring effective adaptation strategies to bear. I also fear that those of us in wealthier countries might not respond with the requisite humanity to help – what would that mean for us?

It’s frustrating that we seem to be in possession of all the understanding ad solutions to change our destructive ways and deal with the consequences of them, but there is a collective lack of will to do it. I feel helpless because I feel poorly equipped to stir people or our leaders to force change.

But I try, will continue to try, and I hope you will too.

I feel sad, ashamed, fearful, and often frustrated and helpless.

I see current climate change as part of a wider human caused environmental depreciation and it saddens me how we behave towards the natural environment. I’m ashamed about what we are knowingly doing to our planet. Especially when, for me, and I imagine many others, being in the natural environment is one of the greatest sources of solace and joy to be had.

I live in a small home, use green energy, turn off the lights, share my car and prefer my bike over it, eat meat only rarely, avoid packaging if I can, and so on. But my whole lifestyle is still a kind of aberration of the natural systems we evolved in. Am I doing enough? Enough to legitimately ask others to do something too? Probably not.

I’m afraid we will wait too long to make the wholesale changes in attitudes and governance needed to improve our situation. As a result, I fear for the future of people in countries too poor to bring effective adaptation strategies to bear. I also fear that those of us in wealthier countries might not respond with the requisite humanity to help – what would that mean for us?

It’s frustrating that we seem to be in possession of all the understanding ad solutions to change our destructive ways and deal with the consequences of them, but there is a collective lack of will to do it. I feel helpless because I feel poorly equipped to stir people or our leaders to force change.

But I try, will continue to try, and I hope you will too.

Professor Emeritus Neville Nicholls

School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment

Monash University

School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment

Monash University

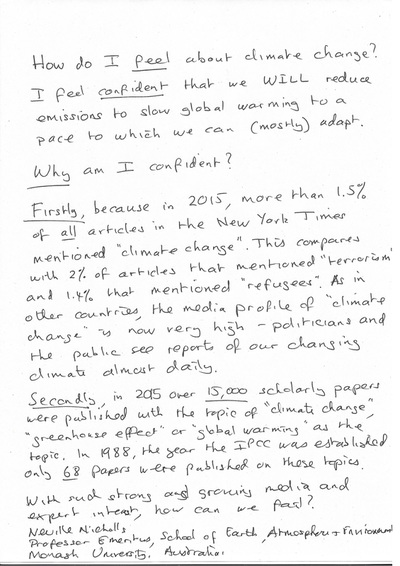

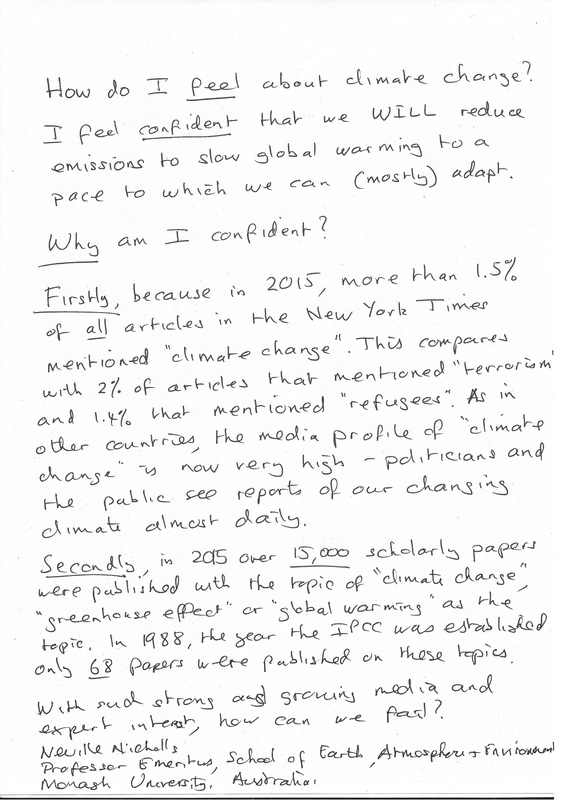

How do I feel about climate change?

I feel confident that we WILL reduce emissions to slow global warming to a pace to which we can (mostly) adapt.

Why am I so confident?

Firstly, because in 2015, more than 1.5% of all articles in the New York Times mentioned “climate change”. This compares with 2% of articles that mentioned “terrorism” and 1.4% that mentioned “refugees”. As in other countries, the media profile of “climate change” is now very strong – politicians and the public see reports about our changing climate almost daily.

Secondly, in 2015 over 15,000 scholarly papers were published with the topic of “climate “change”, “greenhouse effect”, or “global warming” as the topic. In 1988, the year the IPCC was established, only 68 scholarly articles published on these topics.

With such strong and growing media and expert interest, how can we fail?

Neville Nicholls Professor Emeritus, School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment Monash University, Australia

I feel confident that we WILL reduce emissions to slow global warming to a pace to which we can (mostly) adapt.

Why am I so confident?

Firstly, because in 2015, more than 1.5% of all articles in the New York Times mentioned “climate change”. This compares with 2% of articles that mentioned “terrorism” and 1.4% that mentioned “refugees”. As in other countries, the media profile of “climate change” is now very strong – politicians and the public see reports about our changing climate almost daily.

Secondly, in 2015 over 15,000 scholarly papers were published with the topic of “climate “change”, “greenhouse effect”, or “global warming” as the topic. In 1988, the year the IPCC was established, only 68 scholarly articles published on these topics.

With such strong and growing media and expert interest, how can we fail?

Neville Nicholls Professor Emeritus, School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment Monash University, Australia

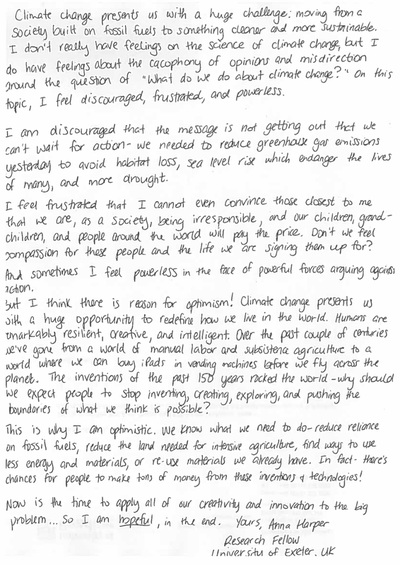

Dr Anna Harper

Research Fellow

University of Exeter

Research Fellow

University of Exeter

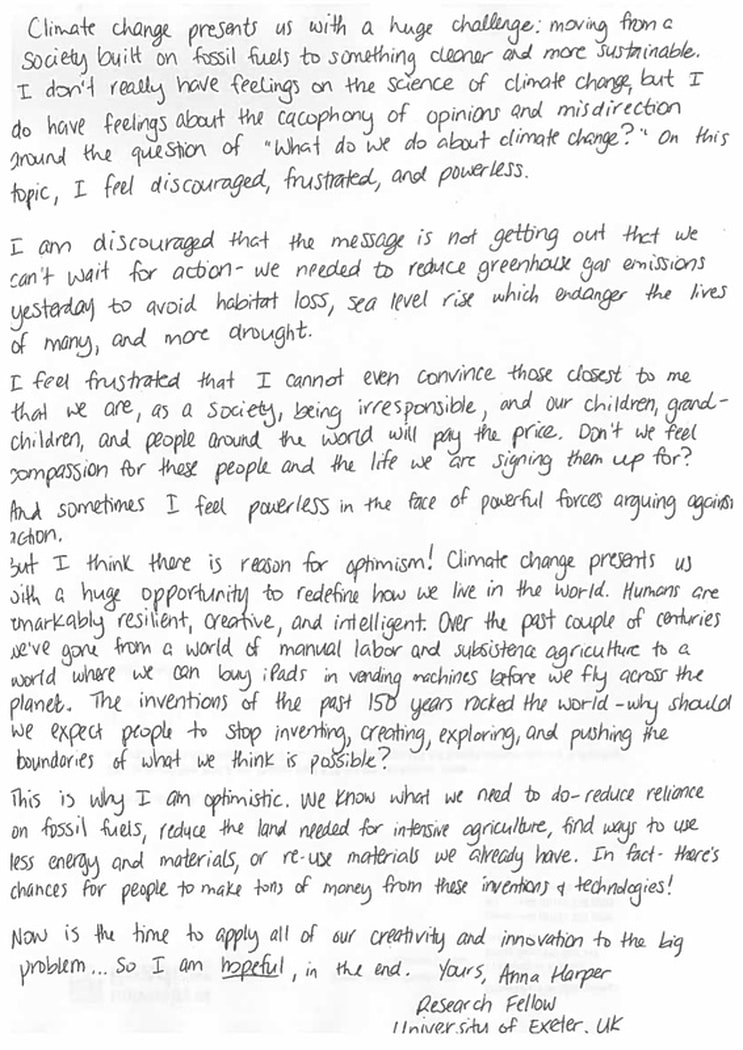

Climate change presents us with a huge challenge: moving from a society built on fossil fuels to something cleaner and more sustainable. I don’t really have feelings on the science of climate change, but I do have feelings about the cacophony of opinions and misdirection around the question of “what do we do about climate change?” On this topic, I feel discouraged, frustrated, and powerless.

I am discouraged that the message is not getting out that we cant wait for action – we needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions yesterday to avoid habitat loss, sea level rise which endanger the lives of many, and more drought.

I feel frustrated that I cannot even convince those closest to me that we are, as a society, being irresponsible, and our children, grandchildren, and people around the world will pay the price. Don’t we feel compassion for these people and the life we are signing them up for?

And sometimes I feel powerless in the face of powerful forces arguing against action.

But I think there is reason for optimism! Climate change presents us with a huge opportunity to redefine how we live in the world. Humans are remarkably resilient, creative and intelligent. Over the past couple of centuries we’ve gone from a world of manual labor and subsistence agriculture to a world where we can buy iPads in vending machines before we fly across the planet. The inventions of the past 150 years rocked the world – why should we expect people to stop inventing, creating, exploring, and pushing the boundaries of what we think is possible?

This is why I am optimistic. We know what we need to do- reduce reliance on fossil fuels, reduce the land needed for intensive agriculture, find ways to use less energy and materials, or re-use materials we already have. In fact – there’s chances for people to make tons of money from these inventions and technologies!

Now is the time to apply all of our creativity and innovation to the big problem… So I am hopeful, in the end.

Yours,

Anna Harper

Research Fellow

University of Exeter, UK

I am discouraged that the message is not getting out that we cant wait for action – we needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions yesterday to avoid habitat loss, sea level rise which endanger the lives of many, and more drought.

I feel frustrated that I cannot even convince those closest to me that we are, as a society, being irresponsible, and our children, grandchildren, and people around the world will pay the price. Don’t we feel compassion for these people and the life we are signing them up for?

And sometimes I feel powerless in the face of powerful forces arguing against action.

But I think there is reason for optimism! Climate change presents us with a huge opportunity to redefine how we live in the world. Humans are remarkably resilient, creative and intelligent. Over the past couple of centuries we’ve gone from a world of manual labor and subsistence agriculture to a world where we can buy iPads in vending machines before we fly across the planet. The inventions of the past 150 years rocked the world – why should we expect people to stop inventing, creating, exploring, and pushing the boundaries of what we think is possible?

This is why I am optimistic. We know what we need to do- reduce reliance on fossil fuels, reduce the land needed for intensive agriculture, find ways to use less energy and materials, or re-use materials we already have. In fact – there’s chances for people to make tons of money from these inventions and technologies!

Now is the time to apply all of our creativity and innovation to the big problem… So I am hopeful, in the end.

Yours,

Anna Harper

Research Fellow

University of Exeter, UK

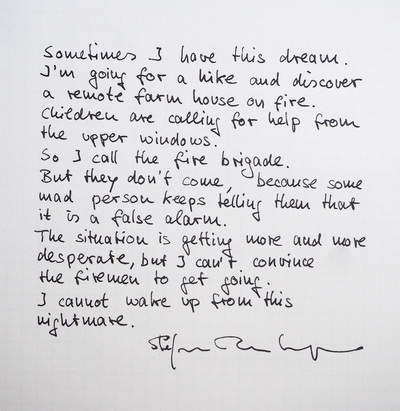

Professor Stefan Rahmstorf

Head of Earth System Analysis

Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

Head of Earth System Analysis

Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

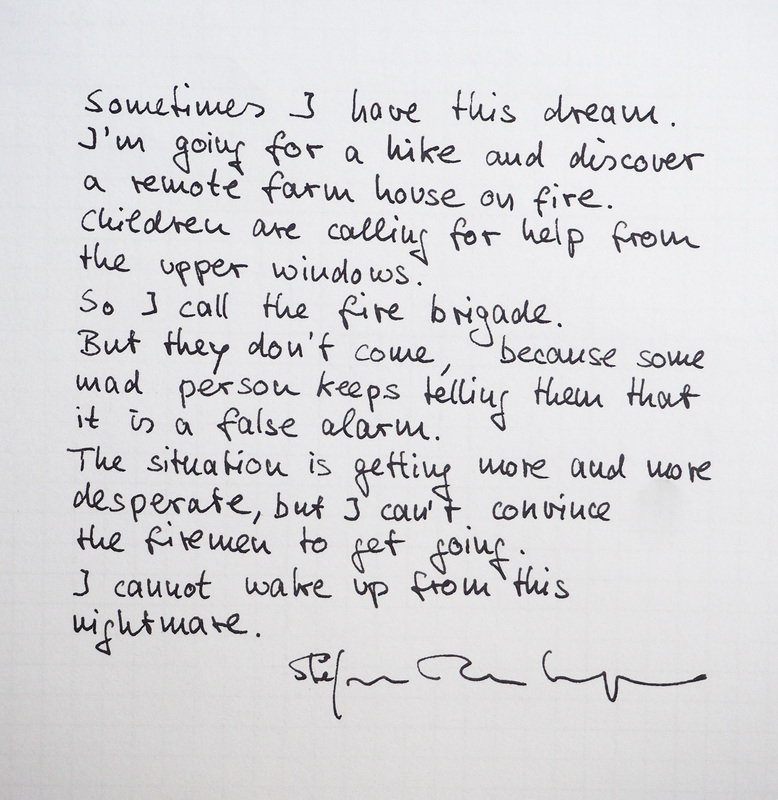

Sometimes I have this dream.

I’m going for a hike and discover a remote farm house on fire.

Children are calling for help from the upper windows. So I call the fire brigade. But they don’t come, because some mad person keeps telling them that it is a false alarm.

The situation is getting more and more desperate, but I cant convince the firemen to get going.

I cannot wake up from this nightmare.

Stefan Rahmstorf.

I’m going for a hike and discover a remote farm house on fire.

Children are calling for help from the upper windows. So I call the fire brigade. But they don’t come, because some mad person keeps telling them that it is a false alarm.

The situation is getting more and more desperate, but I cant convince the firemen to get going.

I cannot wake up from this nightmare.

Stefan Rahmstorf.

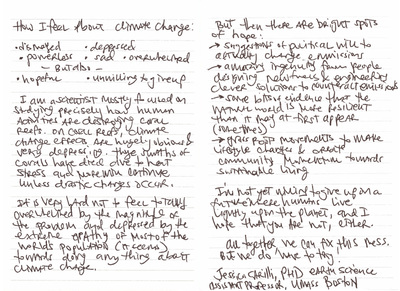

Dr Jessica Carilli

Assistant Professor

University of Massachusetts Boston

Assistant Professor

University of Massachusetts Boston

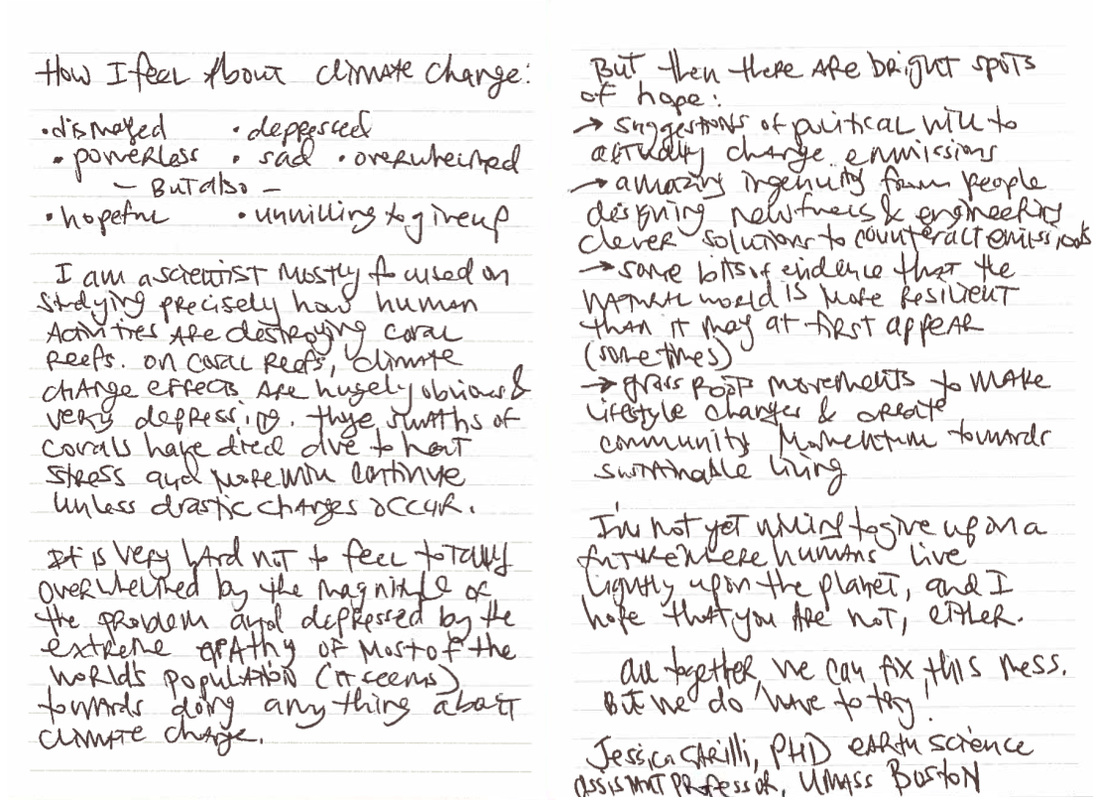

How I feel about climate change:

· Dismayed

· Depressed

· Powerless

· Sad

· Overwhelmed

-But also-

· Hopeful

· Unwilling to give up

I am a scientist mostly focussed on studying precisely how human activities are destroying coral reefs. On coral reefs climate change effects are hugely obvious and very depressing. Huge swaths of coral have died due to heat stress and more will continue unless drastic changes occur.

It is very hard not to feel totally overwhelmed buy the magnitude of the problem and depressed by the extreme apathy of most of the worlds population (it seems) towards doing anything about climate change.

But then there are bright spots of hope:

- Suggestions of political will to actually change emissions.

- Amazing ingenuity from people designing new fuels and engineering clever solutions to counteract emissions.

- Some bits of evidence that the natural world is more resilient than it may at first appear (sometimes).

- Grass roots movements to make lifestyle changes and create community momentum towards sustainable living.

I’m not yet willing to give up on a future where humans live lightly upon the planet, and I hope that you are not, either.

All together we can fix this mess. But we do need to try!

Jessica Carilli, PhD Earth Science

Assistant Professor, UMass Boston.

· Dismayed

· Depressed

· Powerless

· Sad

· Overwhelmed

-But also-

· Hopeful

· Unwilling to give up

I am a scientist mostly focussed on studying precisely how human activities are destroying coral reefs. On coral reefs climate change effects are hugely obvious and very depressing. Huge swaths of coral have died due to heat stress and more will continue unless drastic changes occur.

It is very hard not to feel totally overwhelmed buy the magnitude of the problem and depressed by the extreme apathy of most of the worlds population (it seems) towards doing anything about climate change.

But then there are bright spots of hope:

- Suggestions of political will to actually change emissions.

- Amazing ingenuity from people designing new fuels and engineering clever solutions to counteract emissions.

- Some bits of evidence that the natural world is more resilient than it may at first appear (sometimes).

- Grass roots movements to make lifestyle changes and create community momentum towards sustainable living.

I’m not yet willing to give up on a future where humans live lightly upon the planet, and I hope that you are not, either.

All together we can fix this mess. But we do need to try!

Jessica Carilli, PhD Earth Science

Assistant Professor, UMass Boston.

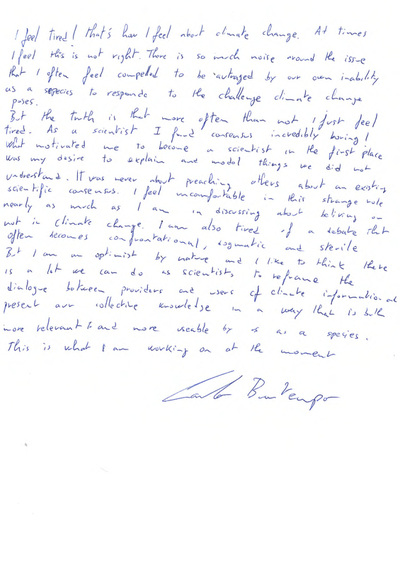

Dr Carlo Buontempo

European Climate Service Team Leader

Met Office Hadley Centre

European Climate Service Team Leader

Met Office Hadley Centre

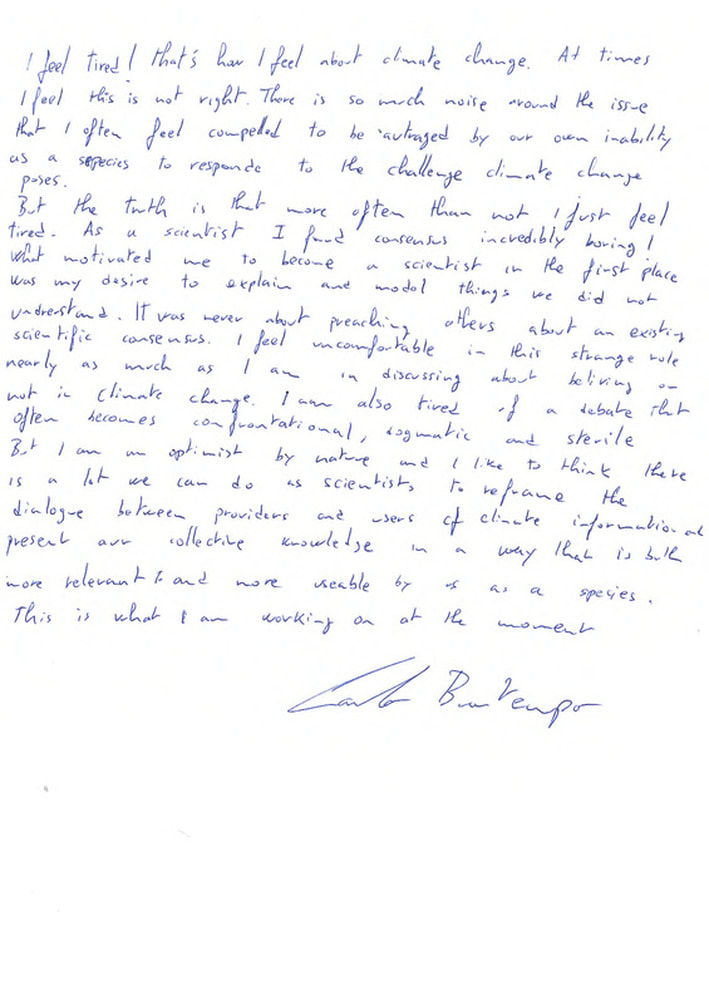

I feel tired!

This is how I feel about climate change. At times I think this is not right. There is so much noise around the issue that I often feel compelled to be outraged by our own inability as a species to response to the challenge climate change poses. But the truth is that more often than not I just feel tired.

As a scientist I found consensus incredibly boring! What motivated me to become a scientist in the first place was my desire to explain and model things we did not understand. It was never about preaching others about an existing scientific consensus. I feel uncomfortable in this strange role nearly as much as I am in discussing about believing or not in climate change. I am also tired of a debate that often becomes confrontational, dogmatic and sterile.

But I am an optimist by nature and I like to think there is a lot we can do as scientists to reframe the dialogue between providers and users of climate information and present our collective knowledge in a way that is both more relevant and usable by us as a species. This is what I am working on at the moment.

Carlo Buontempo

This is how I feel about climate change. At times I think this is not right. There is so much noise around the issue that I often feel compelled to be outraged by our own inability as a species to response to the challenge climate change poses. But the truth is that more often than not I just feel tired.

As a scientist I found consensus incredibly boring! What motivated me to become a scientist in the first place was my desire to explain and model things we did not understand. It was never about preaching others about an existing scientific consensus. I feel uncomfortable in this strange role nearly as much as I am in discussing about believing or not in climate change. I am also tired of a debate that often becomes confrontational, dogmatic and sterile.

But I am an optimist by nature and I like to think there is a lot we can do as scientists to reframe the dialogue between providers and users of climate information and present our collective knowledge in a way that is both more relevant and usable by us as a species. This is what I am working on at the moment.

Carlo Buontempo

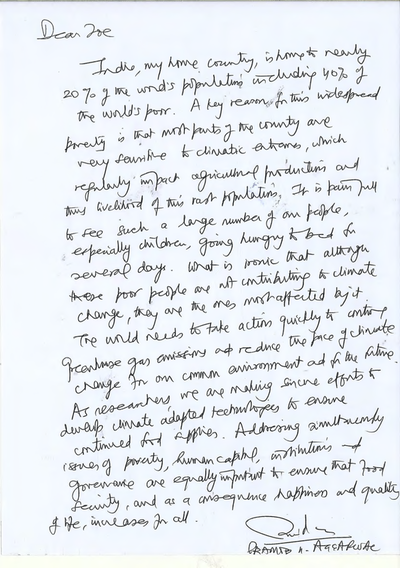

Agus Santoso

Senior Research Associate

University of New South Wales

Senior Research Associate

University of New South Wales

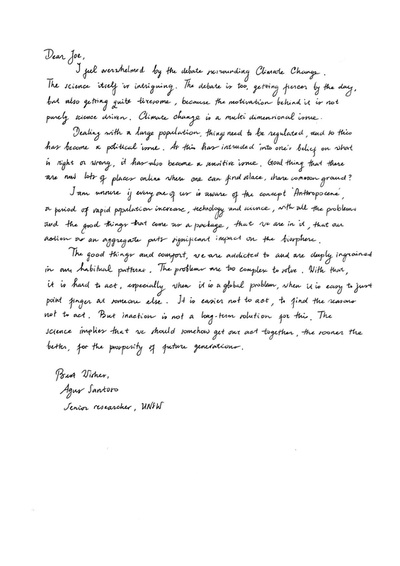

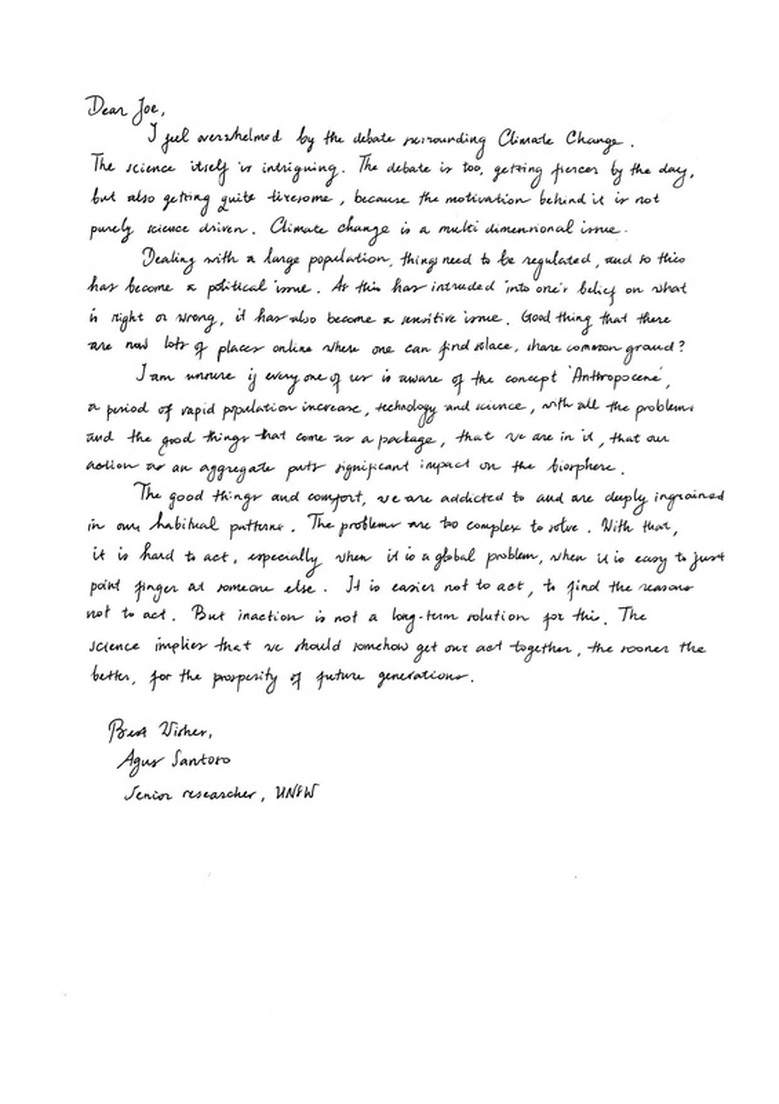

I feel overwhelmed by the debate surrounding Climate Change. The science behind climate change itself is intriguing. The debate is too, getting fiercer by the day, but also getting quite tiresome, because the motivation behind it is not purely science driven. Climate change is a multi-dimensional issue.

Dealing with a large population, things need to be regulated, and so this has become a political issue. As this has intruded into one’s belief on what is right or wrong, it has also become a sensitive issue. Good thing that there are now lots of places online where one can find solace, share common ground?

I am unsure if every one of us is aware of the concept ‘Anthropocene’, a period of rapid population increase, technology and science, with all the problems and the good things that come as a package, that we are in it, that our action as an aggregate puts significant impact on the biosphere.

The good things and comfort, we are addicted to and are deeply ingrained in our habitual patterns. The problems are too complex to solve. With that, it is hard to act, especially when it is a global problem, when it is easy to just point finger at someone else. It is easier not to act, to find the reasons not to act. But inaction is not a long-term solution for this. The science implies that we should somehow get our act together, the sooner the better, for the prosperity of future generations.

Best wishes,

Agus Santoso

Senior researcher, UNSW

Dealing with a large population, things need to be regulated, and so this has become a political issue. As this has intruded into one’s belief on what is right or wrong, it has also become a sensitive issue. Good thing that there are now lots of places online where one can find solace, share common ground?

I am unsure if every one of us is aware of the concept ‘Anthropocene’, a period of rapid population increase, technology and science, with all the problems and the good things that come as a package, that we are in it, that our action as an aggregate puts significant impact on the biosphere.

The good things and comfort, we are addicted to and are deeply ingrained in our habitual patterns. The problems are too complex to solve. With that, it is hard to act, especially when it is a global problem, when it is easy to just point finger at someone else. It is easier not to act, to find the reasons not to act. But inaction is not a long-term solution for this. The science implies that we should somehow get our act together, the sooner the better, for the prosperity of future generations.

Best wishes,

Agus Santoso

Senior researcher, UNSW

Professor Donald J. Wuebbles

Professor of Atmospheric Sciences

University of Illinois

Professor of Atmospheric Sciences

University of Illinois

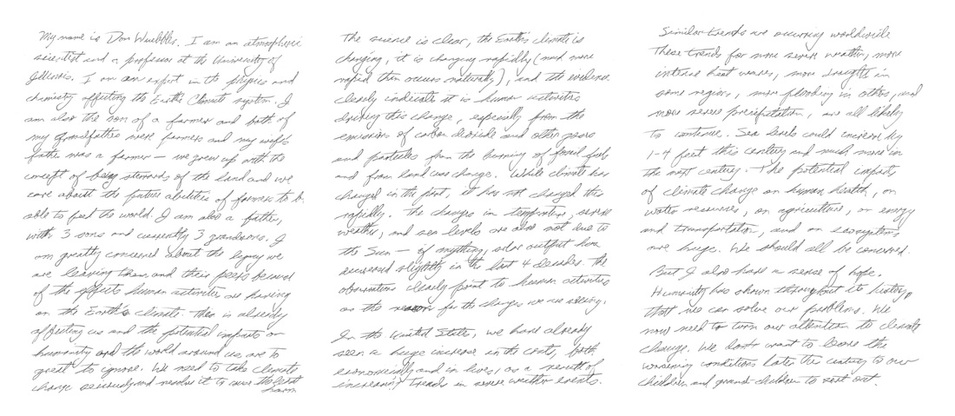

My name is Don Wuebbles. I am an atmospheric scientist and a professor at the University of Illinois. I am an expert in the physics and chemistry affecting the Earths climate system. I am also the son of a farmer and both of my grandfathers were farmers and my wife’s farther was a farmer – we grew up with the concept of being stewards of the land and we care about the future abilities of farmers to be able to feed the world. I am also a father, with 3 sons and currently 3 grandsons. I am greatly concerned about the legacy we are leaving them and their peers because of the effects human activities are having on the Earth’s Climate. This is already affecting us and the potential impacts on humanity and the world around us are too great to ignore.

We need to take climate change seriously and resolve it to cause the least harm.

The science is clear, the Earth’s climate is changing, it is changing rapidly (much more rapid than occurs naturally), and the evidence clearly indicates it is human activities driving this change, especially from the burning of fossil fuels and from land use change. While climate has changed in the past, it has not changed this rapidly. The change in temperature, severe weather, and sea levels are also not due to the sun – if anything, solar output has decreased slightly in the last 4 decades. The observations clearly point to human activities as the reason for the changes we are seeing.

In The United States, we have already seen a huge increase in the costs, both economically and in lives, as a result of increasing trends in severe weather events.

Similar trends are occurring worldwide, these trends for more severe weather, more intense heat waves, more droughts in some regions, more flooding in others, and more severe precipitation, are all likely to continue. Sea levels could increase by 1-4 feet this century. The potential impacts of climate change on human health, on water resources, on agriculture, on energy and transportation, and on ecosystems are huge. We should all be concerned.

But I also have a sense of hope. Humanity has shown throughout history that we can solve our problems. We now need to turn our attention to climate change. We don’t want to leave the warming conditions late this century to our children and grandchildren to sort out.

We need to take climate change seriously and resolve it to cause the least harm.

The science is clear, the Earth’s climate is changing, it is changing rapidly (much more rapid than occurs naturally), and the evidence clearly indicates it is human activities driving this change, especially from the burning of fossil fuels and from land use change. While climate has changed in the past, it has not changed this rapidly. The change in temperature, severe weather, and sea levels are also not due to the sun – if anything, solar output has decreased slightly in the last 4 decades. The observations clearly point to human activities as the reason for the changes we are seeing.

In The United States, we have already seen a huge increase in the costs, both economically and in lives, as a result of increasing trends in severe weather events.

Similar trends are occurring worldwide, these trends for more severe weather, more intense heat waves, more droughts in some regions, more flooding in others, and more severe precipitation, are all likely to continue. Sea levels could increase by 1-4 feet this century. The potential impacts of climate change on human health, on water resources, on agriculture, on energy and transportation, and on ecosystems are huge. We should all be concerned.

But I also have a sense of hope. Humanity has shown throughout history that we can solve our problems. We now need to turn our attention to climate change. We don’t want to leave the warming conditions late this century to our children and grandchildren to sort out.

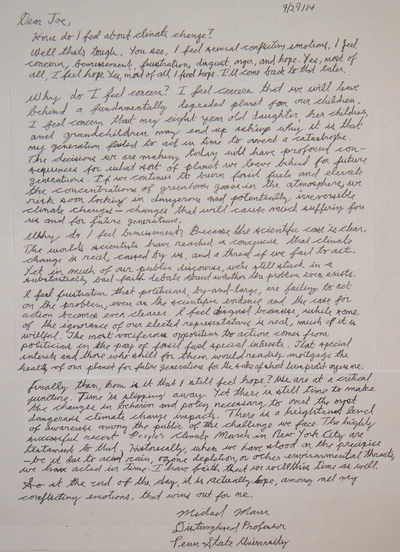

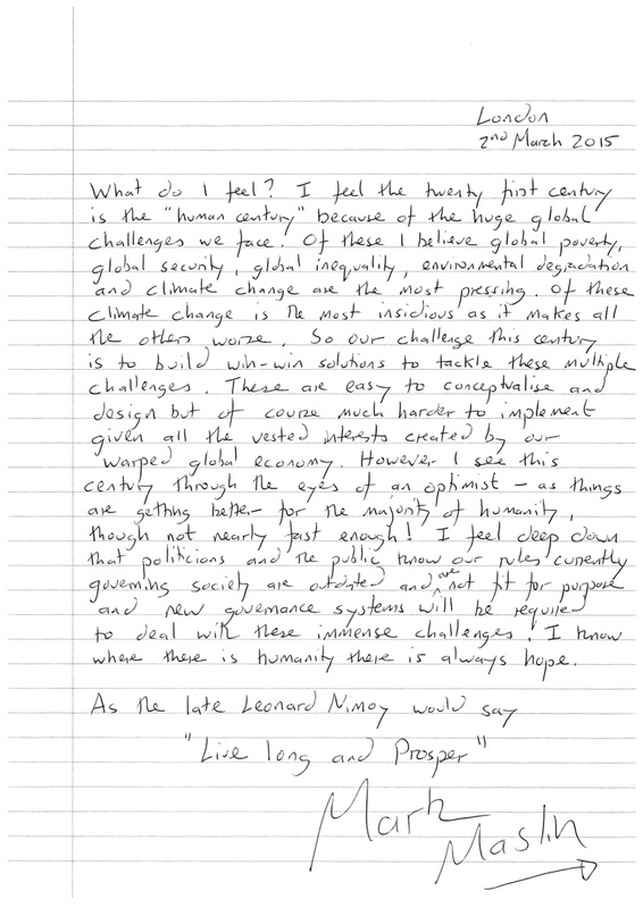

Professor Mark Maslin

Professor of Climatology

University College London

Professor of Climatology

University College London

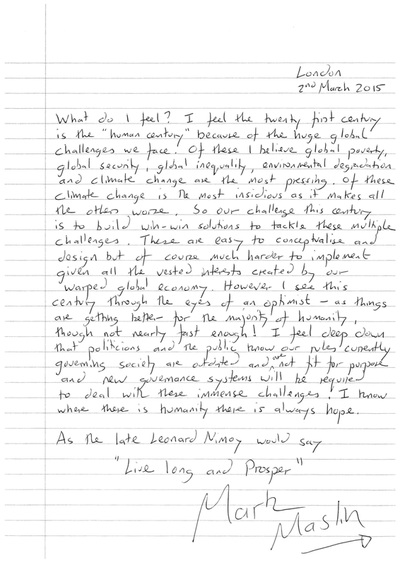

What do I feel?

I feel the twenty first century is the ‘human century’ because of the huge global challenges we face. Of these I believe global poverty, global security, global inequality, environmental degradation and climate change are the most pressing. Of these climate change is the most insidious as it make all the other worse. So our challenge this century is to build win-win solutions that tackle these multiple challenges.

These are easy to conceptualise and design but of course much harder to implement given all the vested interests created by our warped global economy. However I see this century through the eyes of an optimist – as things are getting better for the majority of humanity though not nearly fast enough. I feel deep down that politicians and the public know our rules currently governing society are outdated and not fit for purpose and new governance systems will be required to deal with these immense challenges.

I know where there is humanity there is always hope.

As the late Leonard Nimoy would say

“Live long and prosper”

Mark Maslin

Professor of Climatology

University College London

I feel the twenty first century is the ‘human century’ because of the huge global challenges we face. Of these I believe global poverty, global security, global inequality, environmental degradation and climate change are the most pressing. Of these climate change is the most insidious as it make all the other worse. So our challenge this century is to build win-win solutions that tackle these multiple challenges.

These are easy to conceptualise and design but of course much harder to implement given all the vested interests created by our warped global economy. However I see this century through the eyes of an optimist – as things are getting better for the majority of humanity though not nearly fast enough. I feel deep down that politicians and the public know our rules currently governing society are outdated and not fit for purpose and new governance systems will be required to deal with these immense challenges.

I know where there is humanity there is always hope.

As the late Leonard Nimoy would say

“Live long and prosper”

Mark Maslin

Professor of Climatology

University College London

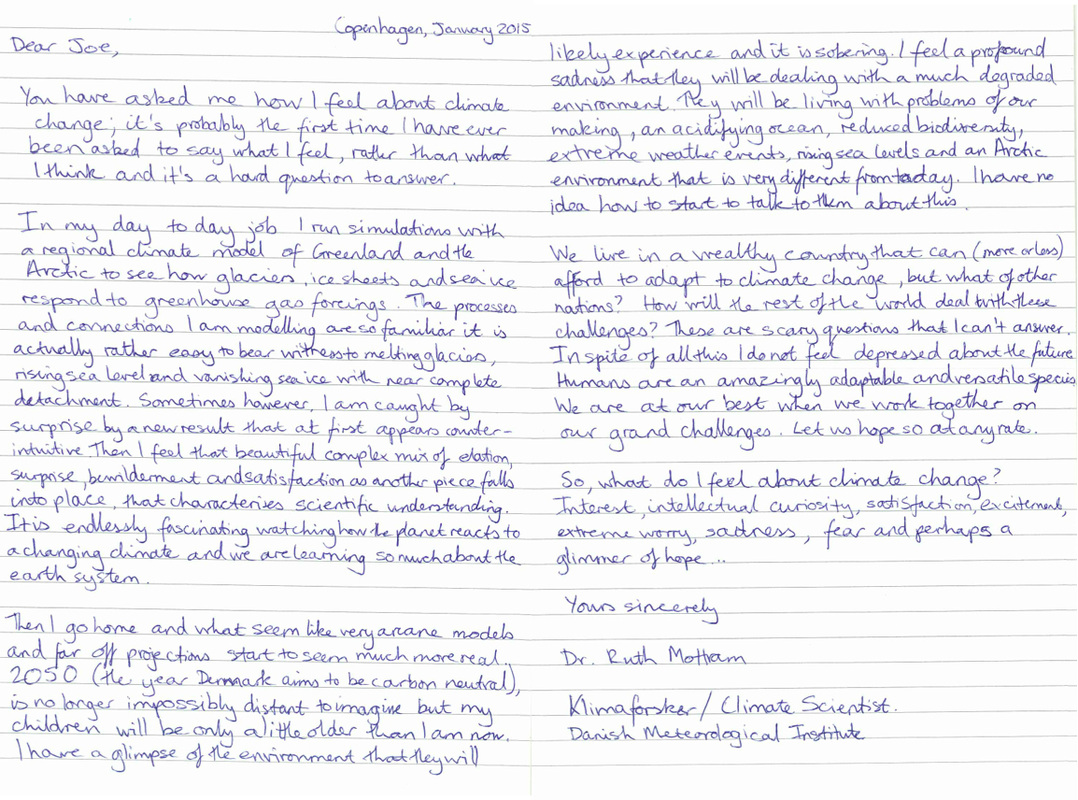

Dr Ruth Mottram

Danish Meteorological Institute

Danish Meteorological Institute

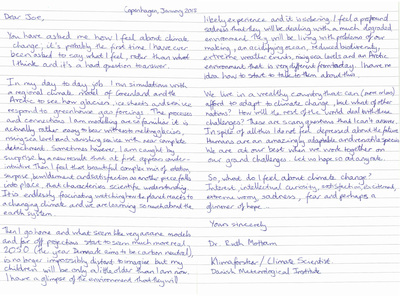

Dear Joe,

You have asked me how I feel about climate change. It’s probably the first time I have ever been asked to say what I feel, rather than what I think and it’s a hard question to answer.

In my day to day job I run simulations with a regional climate model of Greenland and the Arctic to see how glaciers, ice sheets and sea ice respond to greenhouse gas forcings. The processes and connections I am modelling and following are so familiar it is actually rather easy to bear witness to melting glaciers, rising sea level and vanishing sea ice with near complete detachment. Sometimes however, I am caught by surprise by a new result that at first appears counter-intuitive. Then I feel that beautiful complex mix of elation, surprise, bewilderment and satisfaction as another piece falls into place, that characterizes scientific understanding. It is endlessly fascinating watching how the planet reacts to a changing climate and we are learning so much about the earth system.

Then I go home and what seem like very arcane models and far-off projections start to seem much more real. 2050 (the year Denmark aims to become carbon neutral) is no longer impossibly distant to imagine but my children will be only a little older than I am now. I have a glimpse of the possible environment they will likely experience and it is sobering. I feel a profound sadness that they will be dealing with a much degraded environment. They will be living with severe problems of our making, an acidifying ocean, reduced biodiversity, extreme weather events, rising sea levels and an Arctic environment that is very different from today. I have no idea how to start to talk to them about this.

We live in a wealthy country that can (more or less) afford to adapt to climate change, but what of other nations? How will the rest of the world deal with these challenges? These are scary questions that I can’t answer. In spite of all this I do not feel depressed about the future. Humans are an amazingly adaptable and versatile species. We are at our best when we work together on our grand challenges. Let us hope so at any rate.

So, what do I feel about climate change? Interest, intellectual curiosity, satisfaction, excitement, extreme worry, sadness, fear and perhaps a glimmer of hope...

Yours sincerely

Dr Ruth Mottram

Klimaforsker/Climate Scientist

Danish Meteorological Institute

You have asked me how I feel about climate change. It’s probably the first time I have ever been asked to say what I feel, rather than what I think and it’s a hard question to answer.

In my day to day job I run simulations with a regional climate model of Greenland and the Arctic to see how glaciers, ice sheets and sea ice respond to greenhouse gas forcings. The processes and connections I am modelling and following are so familiar it is actually rather easy to bear witness to melting glaciers, rising sea level and vanishing sea ice with near complete detachment. Sometimes however, I am caught by surprise by a new result that at first appears counter-intuitive. Then I feel that beautiful complex mix of elation, surprise, bewilderment and satisfaction as another piece falls into place, that characterizes scientific understanding. It is endlessly fascinating watching how the planet reacts to a changing climate and we are learning so much about the earth system.

Then I go home and what seem like very arcane models and far-off projections start to seem much more real. 2050 (the year Denmark aims to become carbon neutral) is no longer impossibly distant to imagine but my children will be only a little older than I am now. I have a glimpse of the possible environment they will likely experience and it is sobering. I feel a profound sadness that they will be dealing with a much degraded environment. They will be living with severe problems of our making, an acidifying ocean, reduced biodiversity, extreme weather events, rising sea levels and an Arctic environment that is very different from today. I have no idea how to start to talk to them about this.

We live in a wealthy country that can (more or less) afford to adapt to climate change, but what of other nations? How will the rest of the world deal with these challenges? These are scary questions that I can’t answer. In spite of all this I do not feel depressed about the future. Humans are an amazingly adaptable and versatile species. We are at our best when we work together on our grand challenges. Let us hope so at any rate.

So, what do I feel about climate change? Interest, intellectual curiosity, satisfaction, excitement, extreme worry, sadness, fear and perhaps a glimmer of hope...

Yours sincerely

Dr Ruth Mottram

Klimaforsker/Climate Scientist

Danish Meteorological Institute

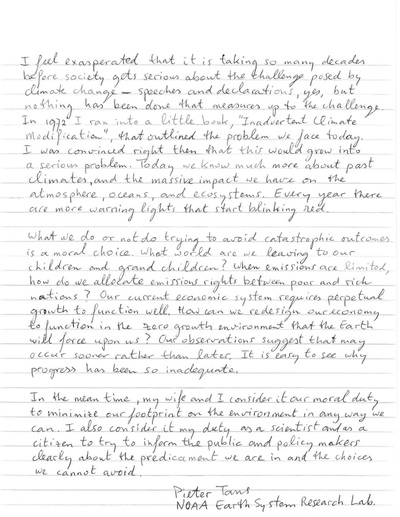

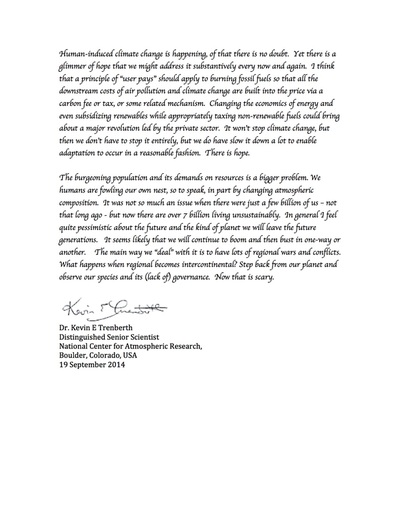

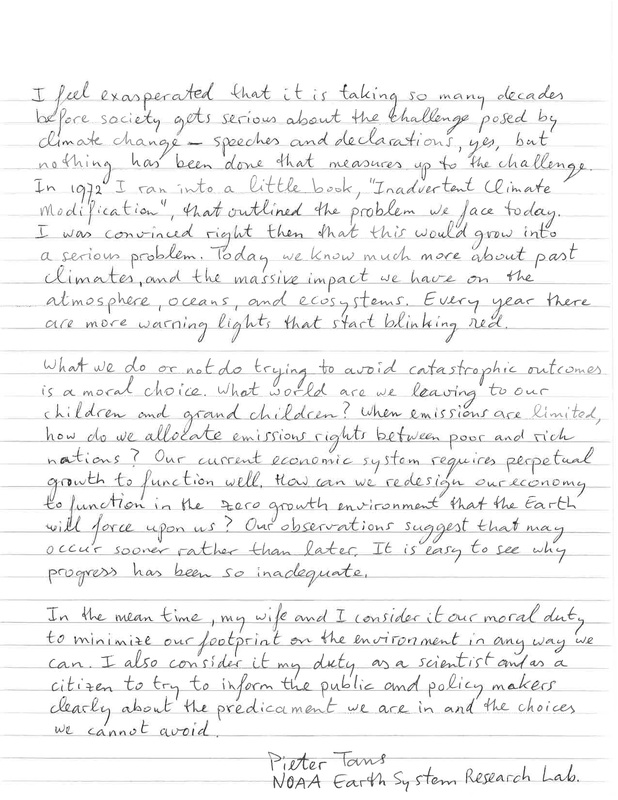

Dr Pieter Tans

Lead scientist, Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network

Earth System Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Lead scientist, Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network

Earth System Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

I feel exasperated that it is taking so many decades before society gets serious about the challenge posed by climate change – speeches and declarations, yes, but nothing has been done that measures up to the challenge. In 1972 I ran into a little book, “Inadvertent Climate Modification”, that outlined the problem we face today. I was convinced right then that this would very likely grow into a serious problem. Today we know much more about past climates and the massive impact we have on the atmosphere, oceans, and ecosystems. Every year there are more warning lights that start blinking red.

What we do or not do trying to avoid catastrophic outcomes is a moral choice. What world are we leaving to our children and grand children? When emissions are limited, how do we allocate emissions rights between poor and rich nations? Our current economic system requires perpetual growth to function well. How can we redesign our economy to function in the zero growth environment that the Earth will force upon us? Our observations suggest that may occur sooner rather than later. It is easy to see why progress has been so inadequate.

In the mean time, my wife and I consider it our moral duty to minimize our footprint on the environment in any way we can. I also consider it my duty as a scientist and as a citizen to try to inform the public and policy makers clearly about the predicament we are in and the choices we cannot avoid.

Pieter Tans

NOAA Earth System Research Lab

What we do or not do trying to avoid catastrophic outcomes is a moral choice. What world are we leaving to our children and grand children? When emissions are limited, how do we allocate emissions rights between poor and rich nations? Our current economic system requires perpetual growth to function well. How can we redesign our economy to function in the zero growth environment that the Earth will force upon us? Our observations suggest that may occur sooner rather than later. It is easy to see why progress has been so inadequate.

In the mean time, my wife and I consider it our moral duty to minimize our footprint on the environment in any way we can. I also consider it my duty as a scientist and as a citizen to try to inform the public and policy makers clearly about the predicament we are in and the choices we cannot avoid.

Pieter Tans

NOAA Earth System Research Lab

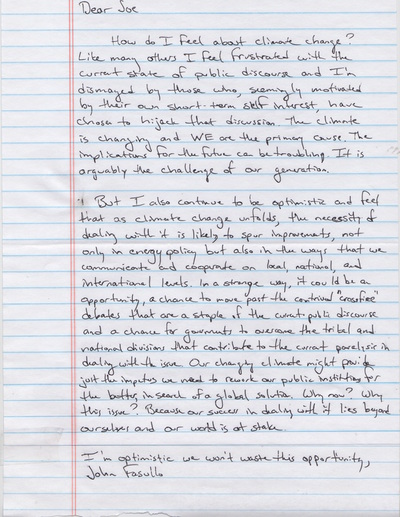

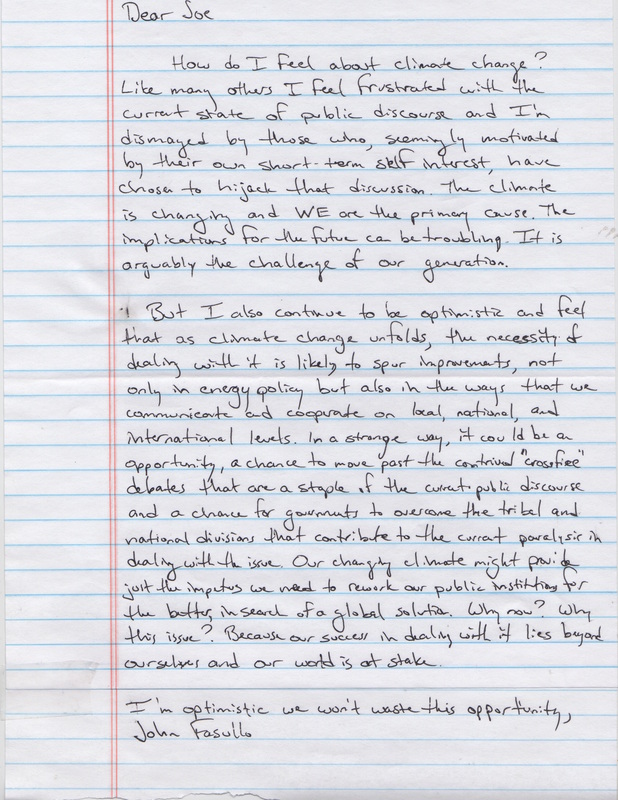

Dr John Fasullo

Project Scientist, Climate analysis section

National Centre for Atmospheric Research

Project Scientist, Climate analysis section

National Centre for Atmospheric Research

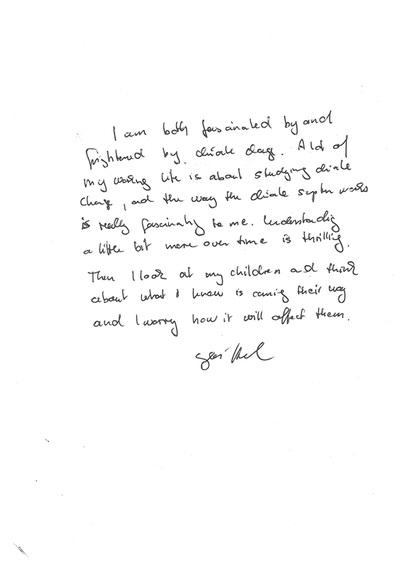

Dear Joe,

How do I feel about climate change?

Like many others I feel frustrated with the current state of public discourse and I’m dismayed by those who, seemingly motivated by their own short-term self interest, have chosen to hijack that discussion. The climate is changing and WE are the primary cause. The implications for the future can be troubling. It is arguably the challenge of our generation.

But I also continue to be optimistic and feel that as climate change unfolds, the necessity of dealing with it is likely to spur improvements, not only in energy policy but also in the ways that we communicate and cooperate on local, national, and international levels. In a strange way, it could be an opportunity, a chance past the controversial “crossfire” debates that are a staple of the current public discourse and a chance for governments to overcome the tribal and national divisions that contribute to the current paralysis in dealing with the issue.

Our changing climate might provide just the impetus we need to rework our public institutions for the better, in search of a global solution. Why now? Why this issue? Because our success in dealing with it lies beyond ourselves and our world is at stake.

I’m optimistic we won’t waste this opportunity.

John Fasullo.

How do I feel about climate change?

Like many others I feel frustrated with the current state of public discourse and I’m dismayed by those who, seemingly motivated by their own short-term self interest, have chosen to hijack that discussion. The climate is changing and WE are the primary cause. The implications for the future can be troubling. It is arguably the challenge of our generation.

But I also continue to be optimistic and feel that as climate change unfolds, the necessity of dealing with it is likely to spur improvements, not only in energy policy but also in the ways that we communicate and cooperate on local, national, and international levels. In a strange way, it could be an opportunity, a chance past the controversial “crossfire” debates that are a staple of the current public discourse and a chance for governments to overcome the tribal and national divisions that contribute to the current paralysis in dealing with the issue.

Our changing climate might provide just the impetus we need to rework our public institutions for the better, in search of a global solution. Why now? Why this issue? Because our success in dealing with it lies beyond ourselves and our world is at stake.

I’m optimistic we won’t waste this opportunity.

John Fasullo.

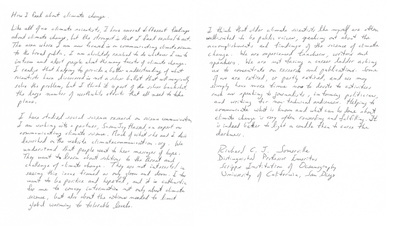

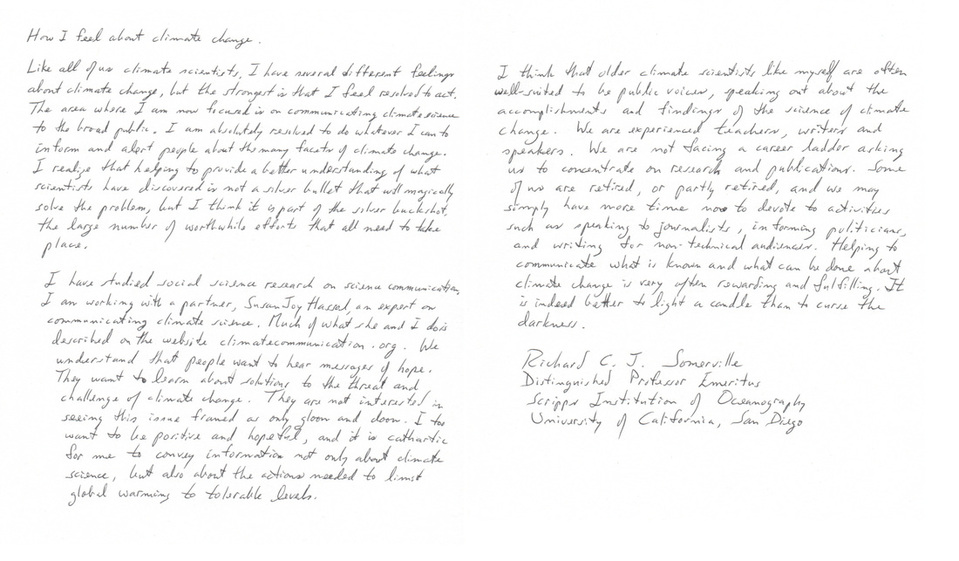

Distinguished Professor Emeritus Richard C. J. Somerville

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

University of California, San Diego

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

University of California, San Diego

How I feel about climate change.

Like all of us climate scientists, I have several different feelings about climate change, but the strongest is that I feel resolved to act. The area where I am now focused is on communicating climate science to the broad public. I am absolutely resolved to do whatever I can to inform and alert people about the many facets of climate change. I realize that helping to provide a better understanding of what scientists have discovered is not a silver bullet that will magically solve the problem, but I think it is part of the silver buckshot, the large number of worthwhile efforts that all need to take place.

I have studied social science research on science communication. I am working with a partner, Susan Joy Hassol, an expert on communicating climate science. Much of what she and I do is described on the website climatecommunication.org. We understand that people want to hear messages of hope. They want to learn about solutions to the threat and challenge of climate change. They are not interested in seeing this issue framed as only gloom and doom. I too want to be positive and hopeful, and it is cathartic for me to convey information not only about climate science, but also about the actions needed to limit global warming to tolerable levels.

I think that older climate scientists like myself are often well-suited to be public voices, speaking out about the accomplishments and findings of the science of climate change. We are experienced teachers, writers and speakers. We are not facing a career ladder asking us to concentrate on research and publications. Some of us are retired, or partly retired, and we may simply have more time now to devote to activities such as speaking to journalists, informing politicians, and writing for non-technical audiences. Helping to communicate what is known and what can be done about climate change is very often rewarding and fulfilling. It is indeed better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.

Richard C. J. Somerville

Distinguished Professor Emeritus

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

University of California, San Diego

Like all of us climate scientists, I have several different feelings about climate change, but the strongest is that I feel resolved to act. The area where I am now focused is on communicating climate science to the broad public. I am absolutely resolved to do whatever I can to inform and alert people about the many facets of climate change. I realize that helping to provide a better understanding of what scientists have discovered is not a silver bullet that will magically solve the problem, but I think it is part of the silver buckshot, the large number of worthwhile efforts that all need to take place.

I have studied social science research on science communication. I am working with a partner, Susan Joy Hassol, an expert on communicating climate science. Much of what she and I do is described on the website climatecommunication.org. We understand that people want to hear messages of hope. They want to learn about solutions to the threat and challenge of climate change. They are not interested in seeing this issue framed as only gloom and doom. I too want to be positive and hopeful, and it is cathartic for me to convey information not only about climate science, but also about the actions needed to limit global warming to tolerable levels.

I think that older climate scientists like myself are often well-suited to be public voices, speaking out about the accomplishments and findings of the science of climate change. We are experienced teachers, writers and speakers. We are not facing a career ladder asking us to concentrate on research and publications. Some of us are retired, or partly retired, and we may simply have more time now to devote to activities such as speaking to journalists, informing politicians, and writing for non-technical audiences. Helping to communicate what is known and what can be done about climate change is very often rewarding and fulfilling. It is indeed better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.

Richard C. J. Somerville

Distinguished Professor Emeritus

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

University of California, San Diego

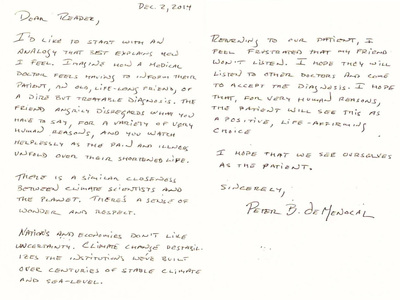

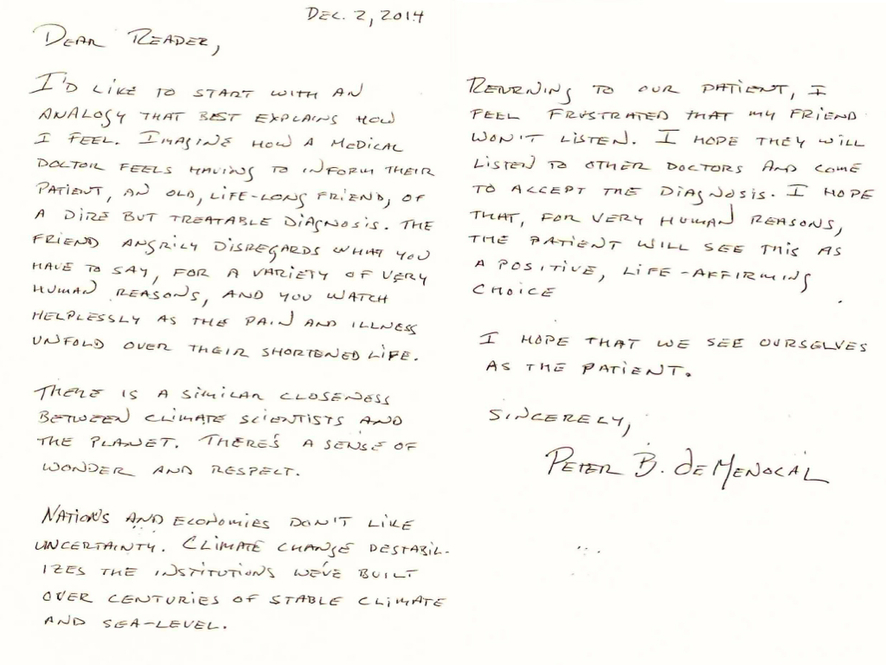

Professor Peter B. deMenocal

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Columbia University

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

Columbia University

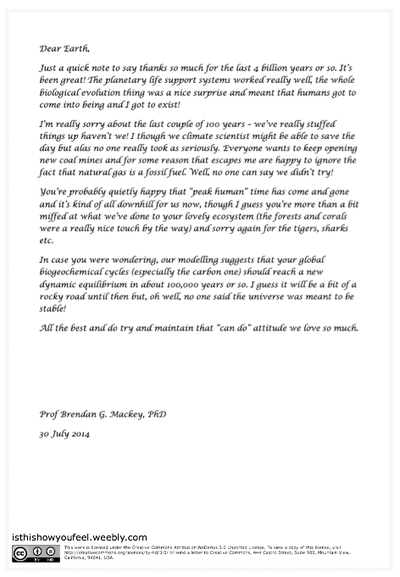

Dear Reader,

I’d like to start with an analogy that best explains how I feel. Imagine how a medical doctor feels having to inform their patient, an old, life-long friend, of a dire but treatable diagnosis. The friend angrily disregards what you have to say, for a variety of very human reasons, and you watch helplessly as the pain and illness unfold over the rest of their shortened life.

There is a similar closeness between climate scientists and the planet. There’s a sense of wonder and respect. Nations and economies don’t like uncertainty. Climate change destabilizes the institutions we’ve built over centuries of stable climate and sea level.

Returning to our patient, I feel frustrated that my friend won’t listen. But I hope they will listen to other doctors and come accept the diagnosis. I hope that, for very human reasons, the patient will see this as a positive, life-affirming choice.

I hope that we see ourselves as the patient.

Sincerely,

Peter B. deMenocal

I’d like to start with an analogy that best explains how I feel. Imagine how a medical doctor feels having to inform their patient, an old, life-long friend, of a dire but treatable diagnosis. The friend angrily disregards what you have to say, for a variety of very human reasons, and you watch helplessly as the pain and illness unfold over the rest of their shortened life.

There is a similar closeness between climate scientists and the planet. There’s a sense of wonder and respect. Nations and economies don’t like uncertainty. Climate change destabilizes the institutions we’ve built over centuries of stable climate and sea level.

Returning to our patient, I feel frustrated that my friend won’t listen. But I hope they will listen to other doctors and come accept the diagnosis. I hope that, for very human reasons, the patient will see this as a positive, life-affirming choice.

I hope that we see ourselves as the patient.

Sincerely,

Peter B. deMenocal

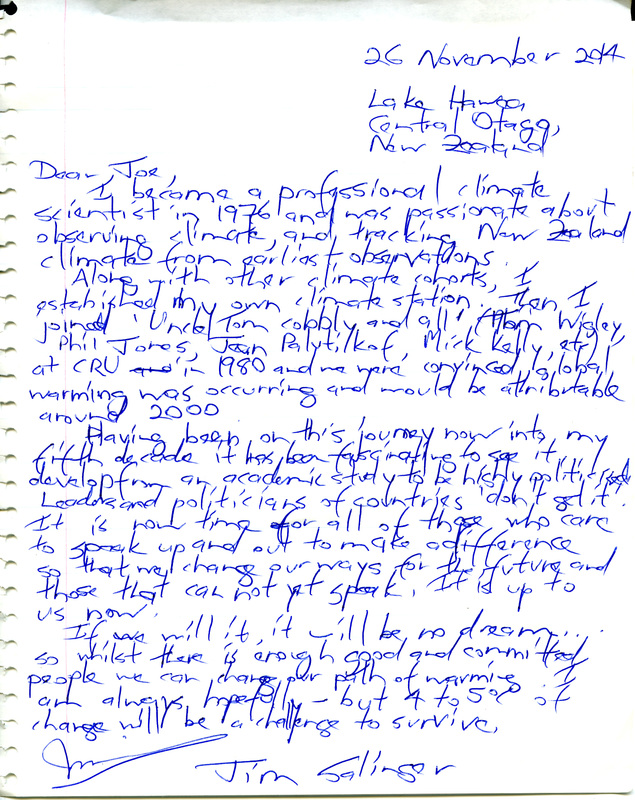

Dr Jim Salinger

Honorary Research Associate in Climate Science, School of Environment

University of Auckland

Honorary Research Associate in Climate Science, School of Environment

University of Auckland

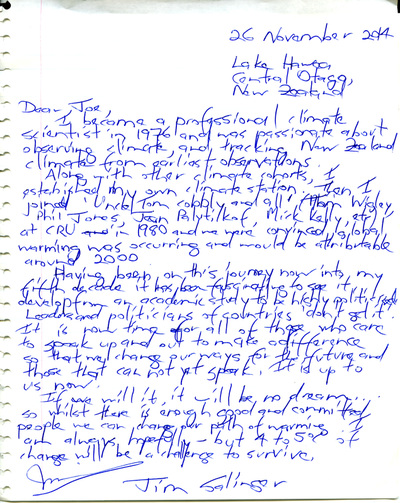

Dear Joe,

I became a professional climate scientist in 1976 and was passionate about observing climate, and tracking New Zealand climate from earliest observations.

Along with other climate cohorts, I established my own climate station. Then I joined ‘Uncle Tom Cobbly and all’ (Tom Wigley, Phil Jones, Jean Palutikof, Mick Kelly, etc.) at CRU in 1980 and we were convinced global warming was real and would be attributable around 2000.

Having been on this journey now into my fifth decade it has been fascinating to see it develop from an academic study to be highly politicised. Leaders and politicians of countries ‘don’t get it’. It is now time for all of those who care to speak up and out to make a difference so that we change our ways for the future abd those that can not yet speak.

It is up to us now.

If we will it, it will be no dream…

So whilst there is enough good and committed people we can change our path of warming. I am always hopeful – but 4 to 5 degrees Celsius of change will be a challenge to survive.

Jim Salinger

I became a professional climate scientist in 1976 and was passionate about observing climate, and tracking New Zealand climate from earliest observations.

Along with other climate cohorts, I established my own climate station. Then I joined ‘Uncle Tom Cobbly and all’ (Tom Wigley, Phil Jones, Jean Palutikof, Mick Kelly, etc.) at CRU in 1980 and we were convinced global warming was real and would be attributable around 2000.

Having been on this journey now into my fifth decade it has been fascinating to see it develop from an academic study to be highly politicised. Leaders and politicians of countries ‘don’t get it’. It is now time for all of those who care to speak up and out to make a difference so that we change our ways for the future abd those that can not yet speak.

It is up to us now.

If we will it, it will be no dream…

So whilst there is enough good and committed people we can change our path of warming. I am always hopeful – but 4 to 5 degrees Celsius of change will be a challenge to survive.

Jim Salinger

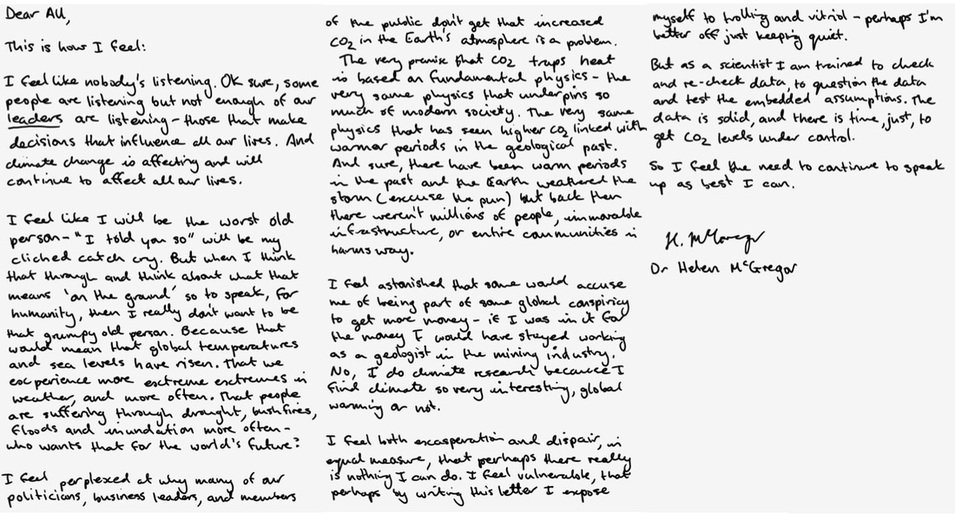

Dr Helen McGregor

Research Fellow, Research School of Earth Sciences

Australian National University

Research Fellow, Research School of Earth Sciences

Australian National University

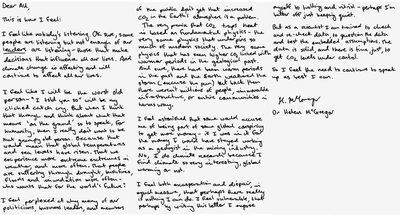

Dear All,

This is how I feel:

I feel like nodbody’s listening. Ok Sure, some people are listening but not enough of our leaders are listening – those that make decisions that influence all our lives. And climate change is affecting and will continue to affect all our lives.

I feel like I will be the worst old person - “I told you so” will be my clichéd catch cry. But when I think that through and think about what that means ‘on the ground’ so to speak, for humanity, then I really don’t want to be that grumpy old person. Because that would mean that global temperatures and sea levels have risen. That we experience more extreme extremes in weather, and more often. That people are suffering through drought, bushfires, floods and inundation more often – who wants that for the world’s future?

I feel perplexed at why many of our politicians, business leaders , and members of the public don’t get that increased CO2 in the Earths atmosphere is a problem. The very premise that CO2 traps heat is based on fundamental physics – the very same physics that underpins so much of modern society. The very same physics that has seen higher C02 linked with warmer periods in the geological past. And sure, there have been warm periods in the past and the Earth weathered the storm (excuse the pun) but back then there weren’t millions of people, immovable infrastructure, or entire communities in harms way.

I feel astonished that some would accuse me of being part of some global conspiracy to get more money – if I was in it for the money I would have stayed working as a geologist in the mining industry. No, I do climate research because I find climate so very interesting, global warming or not.

I feel both exasperation and despair in equal measure, that perhaps there really is nothing I can do. I feel vulnerable, that perhaps by writing this letter I expose myself to trolling and vitriol – perhaps I’m better off just keeping quiet.

But as a scientist I am trained to check and re-check data, to question the data and test the embedded assumptions. The data is solid, and there is time, just, to get CO2 levels under control.

So I feel the need to continue to speak up as best I can.

Dr Helen McGregor

This is how I feel:

I feel like nodbody’s listening. Ok Sure, some people are listening but not enough of our leaders are listening – those that make decisions that influence all our lives. And climate change is affecting and will continue to affect all our lives.

I feel like I will be the worst old person - “I told you so” will be my clichéd catch cry. But when I think that through and think about what that means ‘on the ground’ so to speak, for humanity, then I really don’t want to be that grumpy old person. Because that would mean that global temperatures and sea levels have risen. That we experience more extreme extremes in weather, and more often. That people are suffering through drought, bushfires, floods and inundation more often – who wants that for the world’s future?

I feel perplexed at why many of our politicians, business leaders , and members of the public don’t get that increased CO2 in the Earths atmosphere is a problem. The very premise that CO2 traps heat is based on fundamental physics – the very same physics that underpins so much of modern society. The very same physics that has seen higher C02 linked with warmer periods in the geological past. And sure, there have been warm periods in the past and the Earth weathered the storm (excuse the pun) but back then there weren’t millions of people, immovable infrastructure, or entire communities in harms way.

I feel astonished that some would accuse me of being part of some global conspiracy to get more money – if I was in it for the money I would have stayed working as a geologist in the mining industry. No, I do climate research because I find climate so very interesting, global warming or not.

I feel both exasperation and despair in equal measure, that perhaps there really is nothing I can do. I feel vulnerable, that perhaps by writing this letter I expose myself to trolling and vitriol – perhaps I’m better off just keeping quiet.

But as a scientist I am trained to check and re-check data, to question the data and test the embedded assumptions. The data is solid, and there is time, just, to get CO2 levels under control.

So I feel the need to continue to speak up as best I can.

Dr Helen McGregor

Professor Peter Cox

Theme Leader for Climate Change and Sustainable Futures

University of Exeter

Theme Leader for Climate Change and Sustainable Futures

University of Exeter

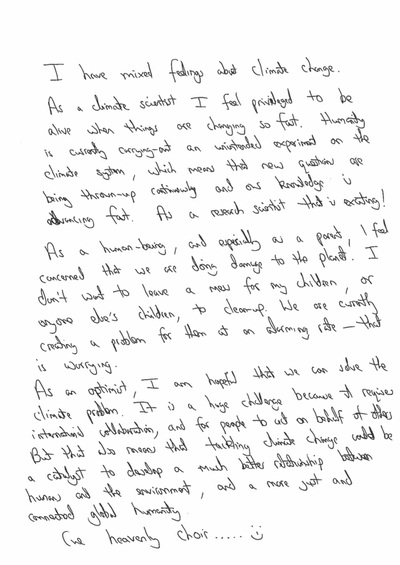

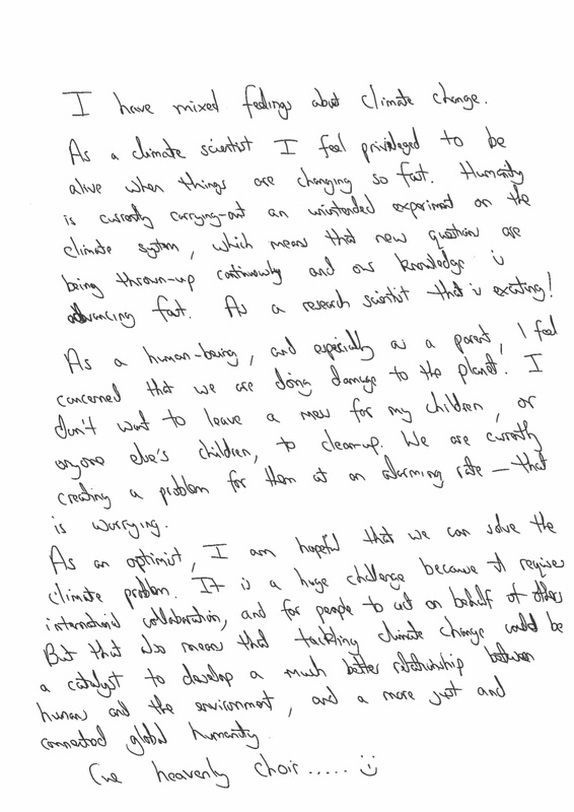

I have mixed feelings about climate change.

As a climate scientist I feel privileged to be alive when things are changing so fast. Humanity is currently carrying out an unintended experiment on the climate system, which means that new questions are being thrown-up continuously and our knowledge is advancing fast. As a research scientist that is exciting!

As a human-being, and especially as a parent, I feel concerned that we are doing damage to the planet. I don’t want to leave a mess for my children, or anyone else’s children, to clear-up. We are currently creating a problem for them at an alarming rate – that is worrying.

As an optimist, I am hopeful that we can solve the climate problem. It is a huge challenge because it requires international collaboration, and for people to act on behalf of others. But that also means that tacking climate change could be a catalyst to develop a much better relationship between humans and the environment, and a more just and connected global humanity.

Cue heavenly choir...:-)

As a climate scientist I feel privileged to be alive when things are changing so fast. Humanity is currently carrying out an unintended experiment on the climate system, which means that new questions are being thrown-up continuously and our knowledge is advancing fast. As a research scientist that is exciting!

As a human-being, and especially as a parent, I feel concerned that we are doing damage to the planet. I don’t want to leave a mess for my children, or anyone else’s children, to clear-up. We are currently creating a problem for them at an alarming rate – that is worrying.

As an optimist, I am hopeful that we can solve the climate problem. It is a huge challenge because it requires international collaboration, and for people to act on behalf of others. But that also means that tacking climate change could be a catalyst to develop a much better relationship between humans and the environment, and a more just and connected global humanity.

Cue heavenly choir...:-)

Professor James Byrne,

Professor of Geography,

University of Lethbridge

Professor of Geography,

University of Lethbridge

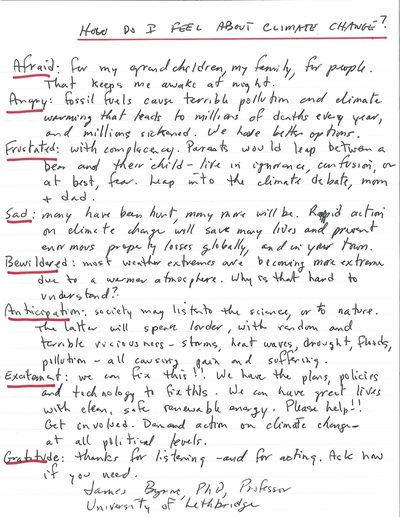

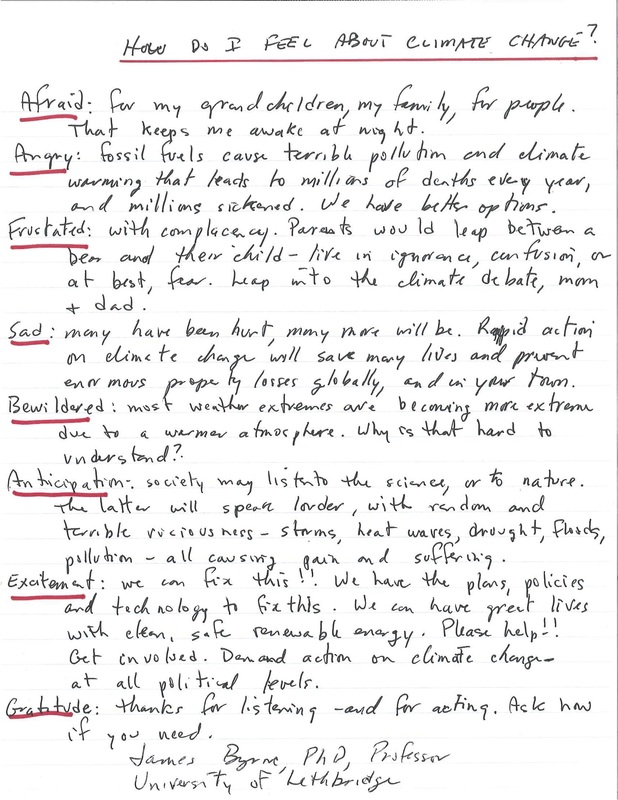

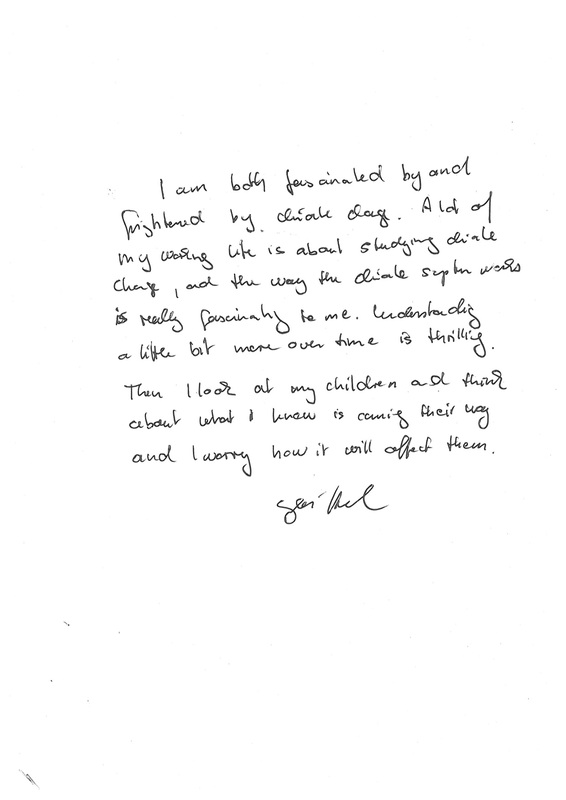

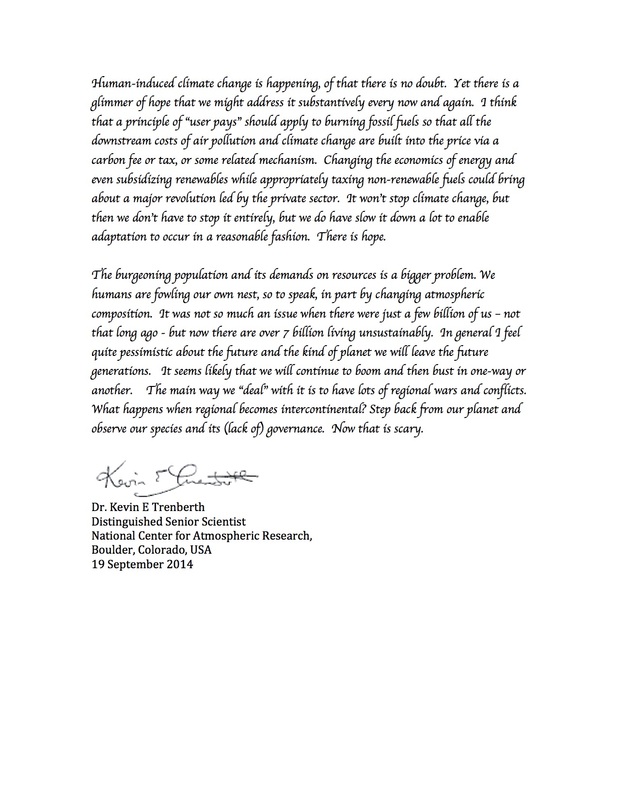

How do I feel about climate change?